Paralleling grassroot memories with historiography

- Update Time : Tuesday, April 2, 2024

- 39 Time View

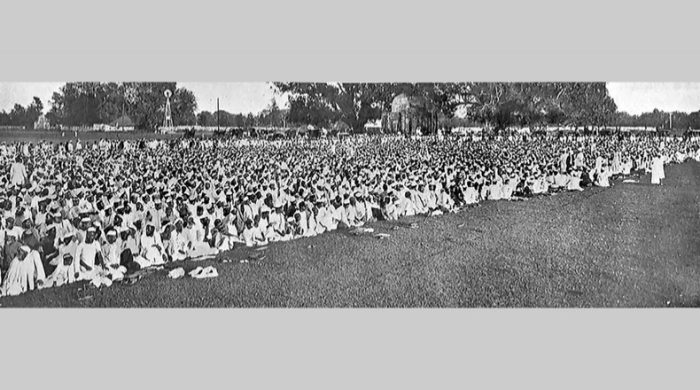

THIS narrative swirls between the mainstream historiography of the 1947 Bengal Partition and the reminiscences of the grassroots Hindu-Muslim encounters on the eve of that epoch-making split. The middle of the 1940s, as I recall, epitomised the jaded sunset of the British Raj in India. Growing out of the British Indian subject status in those days was like staring out of a ‘fracturing chrysalis.’ In their daze of identity muddle, people often, in my localities, distinguished themselves only as Muslims, Hindus, or Christians, not as British Indians, Bengalis, Indians, or Pakistanis. The meandering memories of the past and the living experiences of the time are still Bangladeshi political and social inheritances. They are germane to probe the existing political and intellectual deadlock in contemporary Bangladesh and look at the future with a smidgeon of hope, wisdom, and compassion.

Growing up in a vicinity barely twenty-four miles outside Dhaka, I remember that now and then communal rioting broke out in the city that catapulted Hindu-Muslim tension to our nearby villages. Behind such eruptions, rumours played crucial roles — they drifted from both ends of the communal aisles. Gossips about cow-bones thrown at the Hindu temples or a slaughtered pig tossed at the Muslim household or in the mosque premises could easily spark a riot in Dhaka.

My father recalled the murder news of Nazir Ahmed, a Dhaka University student brutally stabbed to death in 1942. My school observed his death anniversary, even in the late 1940s. At such junctures, emotional rhetoric overshadowed facts. Available memoirs and autobiographies and specks of my recollections validate that in Dhaka, the Hindus and Muslims did not readily live in the same neighbourhoods. My village had only a couple of (Hindu) barber families. I noticed that the Hindu bhadralok concentrated in a segment of the town called Munsefpur — the social interactions between the Hindu and Muslim communities did not usually include inter-dining, marriages, or entering each other’s residential quarters. In fact, that posh residential wedge had an unwritten charter: ‘only the caste Hindus are welcome.’ I socialised with the Hindu classmates from the local bhadralok families, but mostly we assembled in their out-house facilities. The ritual of touching and not touching (choa-choi) sharply alienated Hindu-Muslim socialisation. Personally, I also experienced it in Dhaka while I was a student in the early 1950s. And yet, the annihilation of the Hindus did not dominate the Pakistan Zindabad slogans in Dhaka or in my adjacent villages. Exclusive Hindu-Muslim hatreds did not spread beyond those strips where violent communal clashes peaked. With a Hindu middle class dominating the bureaucracy and professional bodies in Dhaka, the on-again, off-again communal riots were still under control. Notwithstanding occasional disruptions on the Dhaka University campus, the education process did not suffer a disastrous shutdown during the 1940s.

My sense is that the Hindu elite suffered a gradual loss of power in the East Bengal districts where the Muslim population was dominant, and since the ascending Muslim politicians harvested the benefits of an expanded electorate and more legislative power in the 1920s, historian John Broomfield highlighted that phenomenon as the ‘elite conflict’ between the longstanding and privileged Hindu class and the new Muslim influentials. In the middle of the 1940s, the Hindus had undeniable fears of living in Pakistan, a Muslim majority state where undivided Bengal would have been under the assertive Muslim leadership. In fact, Nirad Chaudhury’s autobiography recorded a kind of ‘Muslim fear’ that dawned in the wake of the 1905 Bengal split. Of course, that apprehension has solidified among the Hindu elites since AK Fazlul Huq became the chief minister of Bengal after the 1937 elections under the new Government of India Act, 1935. It was that political dread that veered the Hindu intelligentsia towards a division of Bengal so that most Hindus could enjoy their authority in the Hindu-majority districts. There are sound academic findings on this issue. Joya Chatterjee’s Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition 1947 (2002) challenged the ubiquitous justifications that framed the Muslims as the sole perpetrators of the 1947 Bengal Partition. Her post-modern thesis that Hindu bhadralok politics was responsible for the 1947 Bengal division is well known now. Her insightful history further spilled into The Spoils of Partition. Neither India, Pakistan, nor Bangladesh (2011). Joya’s findings are, however, grounded in the urban tremors of the Hindu bhadralok.

Most academic studies confirm that a truncated Pakistan, as it finally emerged in 1947, was not the endgame of the rising Muslim politics in undivided Bengal and larger India. But the Hindu-Muslim fears grew over the decades of Muslim ascendancy through the 1909 separate electorate, the 1919 India Government Act-initiated reforms, the rejuvenated Muslim League under MA Jinnah, the footsteps of the anti-Zamindar and peasant-oriented Krishak Proja Party, the acrimony over the 1928 Nehru Report and the Communal Award (1932), and the expanded provincial autonomy under the Government of India Act 1935 that ushered in the Muslim-led Bengal cabinet after the 1937 election. Even the 1940 Lahore Resolution was not a blueprint for the 1947 Bengal Partition. At the village level, I remember that my father could not elaborate on a full picture of the expected Pakistan when the local students and teachers sporadically sought to know the details of their future state. Until the last days of the Raj, the Muslim League, as well, did not have a full configuration of the new state beyond the chest-pounding choruses for Pakistan. Even with those inter-communal fears and uncertainties, there was nonetheless an accommodating coexistence between Hindus and Muslims in the places where I grew up. The maximum number of teachers and students at the schools and the traders in the bazaar were Hindus until they started migrating to India.

For my book, Identity of a Muslim family in colonial Bengal: Between memories and Hhistory 2021), I reconstructed my memories and family recollections about the local Hindu community immediately before and after the 1947 partition. My father remembered that Shyama Prashad Mukherjee’s Hindu Mahasabah gained ground among his colleagues in the school and their cohorts in the community. Family recollections hinted that he did not like the Hindu Mahasabah; occasionally, in a teasing tone, he commented, ‘Shyama Prashad Babu is in our town’!

But the remains of the Hindu schoolmates drifted towards Subhash Chandra Bose, although the British government claimed that he died in an aircraft accident. Swayed by a class friend from a prominent Hindu family, I and two other Muslim boys joined the so-called Mahajati Mandir, a small pro-Subhash outfit that operated from my friend’s grandfather’s outer house by the large pond. We practiced marching on the open ground in front of the family library and saluted Bose’s large picture. It was in 1946 or at the beginning of 1947. One of the participating friends warned that the police might arrest us, and we avoided that group when its sponsors fled to West Bengal. I also noticed that our Hindu school friends and our (Hindu) teachers occasionally dressed in lunghi in the bazaar and public places. It was their survival impulse to avoid the Muslim attackers during periodic Hindu-Muslim clashes. My mother discouraged me from wearing dhoti to school because she feared that an assaulter could take me for a Hindu and stab or kidnap me.

My father was apolitical by nature; however, he had a deep commitment to promote education among the local Muslims. It was a slog in the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1944, in class IV with twenty-plus students, only four or five of whom were Muslims, I have distinct memories. The school’s Muslim student population, however, jumped in 1946–47, which made my father happy. There were senior students who went to college after they finished their high school matriculation. They rose through their professional ladders later in East Pakistan. I faintly remember jubilation in my village when two of our young neighbours landed government jobs after they completed their BA degrees in the mid-1940s — one of them got a job at the civil supplies’ department, and his brother became a police sub-inspector. Whisper said that one of them did not actually finish his bachelor’s degree, but it was a patronage job by means of his father’s tadbir through Dhaka’s Nawab family.

Such enthusiasm inspired our villagers to send their children to school. Vibes like those wrought the Pakistan movement in the 1940s. This kind of Muslim heartbeat — not the catastrophic religious ferocity and communal hatred — primarily impelled Bengali Muslim politics at the mass level in the 1940s. Sadly, those voices are lacking in mainstream partition studies, which deserve a fresh look. Memories are not the flawless prism of history, but, as Annie Ernaux, the French Nobel laureate, claimed, as a repository of living experiences, they offer an ‘existential paradigm’ to fathom the bygone encounters.

M Rashiduzzaman is a retired academic who occasionally writes on Bangladesh and its political history. The narrative draws from his ‘Identity of a Muslim family in colonial Bengal: Between memories and history’ (Peter Lang, NYC, 2021) and the forthcoming ‘Parties and Politics in East Pakistan 1947–71: the political inheritances of Bangladesh’, (publication expected later in 2024).