The mystery of India’s ‘missing 54’ soldiers

- Update Time : Monday, January 27, 2020

- 267 Time View

They are called “the missing 54” – Indian soldiers forgotten in the fog of past wars with Pakistan, and who appear to have slipped through the cracks of the rival neighbours’ troubled history.

India and Pakistan have twice gone to war over territory in the disputed region of Kashmir – in 1947-48 and in 1965. Then, in 1971, Pakistan lost a 13-day war to India, resulting in its eastern half – separated from the rest of the country by more than 1,600km (990 miles) of India – emerging as the sovereign nation of Bangladesh.

India believes the 54 soldiers went missing in action and are held in Pakistani prisons. But more than four decades after they disappeared, there’s no clarity over their numbers and fate.

Last July, the Narendra Modi-led BJP government told parliament there were 83 Indian soldiers, including the “missing 54”, in Pakistan’s custody. The rest are possibly soldiers who “strayed across the border” or were captured for alleged espionage. Pakistan has consistently denied holding any Indian prisoners of war.

Chander Suta Dogra, a senior Indian journalist, has researched the story of the missing 54 for several years. She has spoken to retired army officers, bureaucrats and relatives of the soldiers and also accessed letters, newspaper clippings, memoirs, diary entries, photographs and declassified records of India’s foreign ministry. Missing in Action: The prisoners who never came back, her meticulously-researched new book, tries to answer the key question: what happened to these men?

There is no closure for the families of the missing soldiers

Anything really, as Ms Dogra’s research shows.

Were these men actually killed in action? Does India have evidence to prove they were being held in Pakistan? Were they singled out for indefinite detention in Pakistan to be used as future bargaining chips?

Were some of them – as many officers in Pakistan believe – Indian intelligence agents caught for spying? Were they tortured brutally after being caught in Pakistan in contravention of the Geneva Convention – international law governing warfare – making it too difficult or embarrassing for the country to repatriate them? Were some of the missing soldiers killed soon after they were captured?

And why did the Indian government bizarrely “admit” that 15 of the 54 had been “confirmed killed” in two affidavits, submitted to a local court in the early 1990s in response to a petition on missing soldiers? And if that is the case, why does the government today insist that all 54 are still missing?

“It is clear that the government knew some of the missing men were actually dead. Then why did they retain their names on the list? Quite clearly, there is deliberate obfuscation and the government owes it to not just to the relatives of the soldiers, but the people of India to come clean,” says Ms Dogra.

The brother of one of the missing soldiers told me the government had failed in its job.

“In the euphoria over the war victories, we just forgot these soldiers,” he said. “I blame successive governments and the defence establishment for their complete apathy. We even wanted a third party to mediate and get to the truth about these soldiers, but India did not agree to it.”

Yet, this is only part of the story.

Relatives of the missing soldiers have visited Pakistan twice without success

Ms Dogra has unearthed some stories which suggest that some of the “missing 54” were reportedly alive in Pakistani prisons even after the wars ended.

The family of a wireless operator who went missing in the 1965 war, for example, was told by the Indian army in August 1966 that he was dead. But, between 1974 and the early 1980s, three Indian prisoners who were returned by Pakistan told authorities and the family of the missing soldier that he was still alive. Still, nothing happened.

It’s not that there have been no efforts to trace the prisoners and bring them home. The two governments have held talks to seek their release. Successive Indian prime ministers have sought to figure out a solution. War veterans on both sides have campaigned for repatriation. It’s not even the case that there was no exchange of prisoners between the two sides: India repatriated some 93,000 captured Pakistani soldiers after the 1971 war, and Pakistan sent back more than 600 soldiers.

Two groups of relatives – six people in 1983 and 14 in 2007- carrying photographs and other details of the missing men travelled to Pakistan and visited jails without success. Some of them alleged that Pakistan had stonewalled their efforts to meet the prisoners, something the country denied. During the second visit, the relatives said there was “strong evidence of them being alive and in Pakistan”. The Pakistani interior ministry denied this.

“We have repeatedly said that there are no Indian PoWs in Pakistan and we stick by that position,” a spokesperson said in 2007.

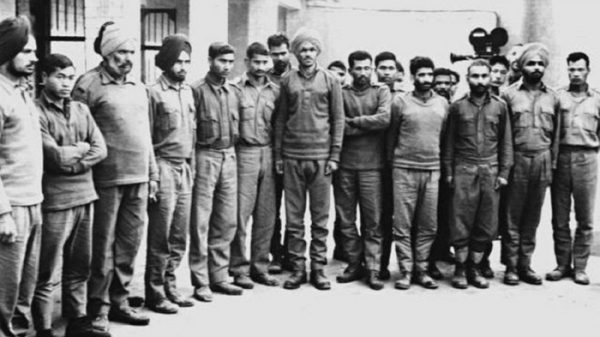

Captured Pakistani soldiers at a prison camp in Bangladesh, 1971

Ms Dogra says the truth lies in the “grey zone where no one wants to tread”.

What is clear is that there is no closure yet for the families of these soldiers.

Take the case of HS Gill, a daredevil air force pilot fondly called “High Speed” Gill by his peers. His plane was shot down over Sindh during the 1971 war. He was 38 when he went missing. His name kept coming up in the lists of missing soldiers that India prepared – and his family believed he would return. He didn’t. Three years ago, his wife, a school principal, died of cancer; his son took his life in his twenties; while the whereabouts of his daughter, according to a family member, are “not known”.

“Frankly, I have not given up hope yet,” the soldier’s brother, Gurbir Singh Gill, told me. “I know he may not be alive. But then we should be told the truth. In absence of the truth you keep hoping that he will come back, don’t you?”

Hope dies hard.