Landless Brazilians and Gaza

- Update Time : Thursday, April 25, 2024

- 39 Time View

THE mass food drive for Gaza was also a campaign to contest the growth of Christian Zionism in the country and deepen ties with the Palestinian struggle.

Brazilian landless workers, who live on settlements and encampments of the Landless Workers’ Movement, gathered roughly 13 tonnes of food to send to Palestinians in Gaza between October and December 2023.

MST cooperatives across the country participated in the solidarity campaign, which included milk from Cooperoeste in Santa Catarina; rice from Terra Livre Cooperative, the Cooperative of Settled Workers of the Porto Alegre Region (Cootap) and Cooperav in Rio Grande do Sul and corn flour from Terra Conquistada in Ceará.

The aid was sent to the Palestinian Agricultural Workers’ Union through the Brazilian Air Force. ‘The Palestinian people, like all the peoples fighting for their sovereignty, need the solidarity actions of other peoples,’ said Jane Cabral of the MST national leadership. Indeed, the world must follow the example of Brazil’s landless workers.

Collecting food has only been one aspect of the MST’s solidarity action with the Palestinian people. The other equally important aspect has been about building a consensus in Brazil regarding Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

Over the past several decades, the right-wing evangelical movement in Latin America has promoted a pro-Israeli political agenda in Brazil and elsewhere.

This movement defends Israel in the hope that it will destroy the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem and build the ‘Third Temple.’

Under this view, the temple will open the door to the return of Christ, and all non-Christians, including Jews, will be subjected to eternal damnation. Evangelical pastors in Latin America — many of them funded by U.S.-based Christian Zionist groups such as Christians United for Israel — have spread this deeply hateful, anti-human view.

This is an important reason why right-wing leaders in the region, including former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and current Argentinian President Javier Milei, are staunch defenders of Israel and the Zionist project.

As such, the MST’s mass drive to collect food for Gaza was also a campaign to contest the growth of Christian Zionism in Brazil, advocate for the rights of the Palestinian people and deepen education about and ties with the Palestinian struggle amongst its base.

The MST, with its nearly 2 million members, is the largest socio-political movement in Latin America and one of the largest peasant movements in the world.

Since it was born 40 years ago, in 1984, the MST has grown steadily because of its unique approach to building and maintaining its base among landless workers.

Tricontinental’s latest dossier, ‘The Political Organisation of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement,’ examines the theoretical orientation that has enabled the MST to build this remarkable organisation on the terrain of Brazil’s wretched social hierarchies, which are rooted in the legacy of Portuguese colonialism, genocide, slavery, and US-backed military dictatorships.

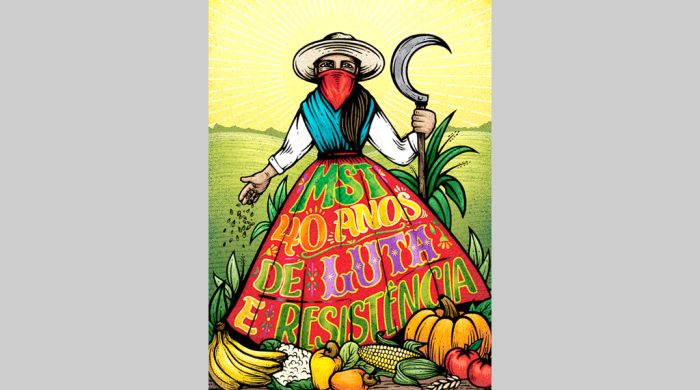

The art for the dossier, which is also featured in this article, was created for the ‘Forty Years of the MST’ call for art organised by the MST, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, ALBA Movements and the International Peoples’ Assembly. The second monthly bulletin from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research’s art department will focus on that exhibition; you can subscribe to it here.

The MST has three goals: to fight for land, to fight for agrarian reform and to transform society. Based on Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, the MST organises landless workers to seize unproductive land and build settlements (assentamentos) and squatters’ encampments (acampamentos).

At present, nearly half a million families live on such settlements and have gained legal tenure of the land, where they have built 1,900 peasant associations, 185 cooperatives and 120 MST-owned agro-industrial sites, with an additional 65,000 families living on encampments and fighting for legal recognition.

It is these institutions that produce the goods sent to Palestine. Despite the unequal balance of forces in Brazil, where the capitalist class enforces its rule over the economy and the countryside through domination of the state, the MST has been able to build its strength over the years and currently operates in 24 of the country’s 26 states. This strength is a product of the MST’s mass base and its organisational methods.

As the dossier explains, a crucial aspect of the MST’s organisational theory is the idea that the assentados, the residents of the agrarian reform settlements, must always be in motion.

There are seven organisational principles that allow the MST to drive this motion: its autonomy in relation to political parties, churches, governments and other institutions, for which organisational unity is essential; the training of organisers both to participate in building the organisation and to be disciplined with respect to the decisions of the collective leadership; the importance of study; and the necessity of internationalism.

The MST does not only fight for land; it also seeks to enact agrarian reform and transform society. In other words, it seeks to change the very nature of agrarian capitalism and construct a model of agroecology that develops a balanced and sustainable form of agriculture — one that harnesses nature rather than degrades it and produces healthy food for society at large.

There are now over 2.4 billion people in the world who are food insecure. More and more famines are breaking out, from Sudan to Palestine, often related to conflicts of different kinds. Meanwhile, we are in the midst of the United Nations Decade of Family Farming, which began in 2019 and will close in 2028.

The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation calculates that family or small farmers produce a third of the world’s food and up to 80 per cent of the food in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Yet these small and family farmers do not control the land that they till, nor do they have the capital to increase their productivity.

As a consequence, many small farmers produce food for the market but not enough to feed their families, leading to an epidemic of hunger amongst millions of small farmers and peasants.

As the FAO notes, ‘The majority of the 600 million farms in the world are small. Farms of less than one hectare account for 70 per cent of all farms but operate only 7 per cent of all agricultural land.’

This great inequality in land ownership is at the heart of the work of the MST, as well as organisations around the world such as Mviwata in Tanzania (about whom Tricontinetal will be publishing a dossier later this year) and the All India Kisan Sabha in India (written about in the June 2021 dossier, ‘The Farmers’ Revolt in India.’)

It is for good reason that the 16 million-member Kisan Sabha, for instance, joined the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement against apartheid Israel in 2017 and why Mviwata, which represents 300,000 peasants, condemned Israel’s genocide of Palestinians at its annual meeting in December 2023.

These farmers and peasants know that their task is not only to redistribute land, but to transform society across the world.

In 1968, Thiago de Mello (1926–2022), born in Brazil’s Amazonas, was sent into exile for his criticism of the military dictatorship. He went to Chile, where he befriended Pablo Neruda.

Before long, de Mello was again forced to flee a military dictatorship, chased out of Chile because of the 1973 coup against the socialist project led by then President Salvador Allende.

De Mello first went to Argentina and then to Europe. It was during this flight, in 1975, that he wrote his classic poem Para os que virão (‘For Those to Come’), the last few lines about the hurt that must be overcome by people who come to fight for social transformation:

It doesn’t matter if it hurts: it’s time

to move forward hand in hand

with those walking in the same direction,

even if it’s a long way off

from learning how to conjugate

the verb to love.

Above all, it’s time

to stop being just

the solitary vanguard

of ourselves.

It’s about meeting.

(The clear truth of our mistakes burns limpid and hard in our chests)

It’s about opening the way.

Those who will come will be the people,

and they will know themselves by fighting.

Consortiumnews.com, April 22. Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian and journalist, is author of 25 books, including The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World and The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South.