Holy war today

- Update Time : Sunday, May 5, 2024

- 36 Time View

‘ISRAELIS are unified to eliminate this evil from the world’, said prime minister Netanyahu in November 2023. ‘You must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible.’ The point was not what Amalekites did to Israelites, but what Israel was told by God to do unto Amalek. ‘Go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; but slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass.’

Many have noted that this is the language of genocide. It is also the language of holy war. In this short article, we write as a scholar of holy war and a scholar of Middle Eastern Studies to consider the kind of peace that is linked to war declared as holy. We do so by rereading some key moments in the western tradition on the holy war in relation to political discourse on war and peace in Gaza and Ukraine.

Peace as war

PEACE is generally considered an ultimate good. But, as was written in the Book of Wisdom (composed in Alexandria not long before the birth of Christ): ‘they call so many and so great evils peace.’ Take the Roman empire, which ‘gave peace unto the world’, to cite the phrase inscribed on Roman medals. The great Roman historian Tacitus put it like this: ‘To ravage, to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire, and where they make a desert, they call it peace [ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant].’

Pax romana brought forth violence, plunder, destruction, and fear. The Romans ‘lived in dark fear and cruel lust’, wrote Augustine, ‘surrounded by the disasters of war and the shedding of blood which, whether that of fellow citizens or enemies, was human nonetheless. The joy of such men may be compared to the fragile splendor of glass: they are horribly afraid lest it be suddenly shattered.’

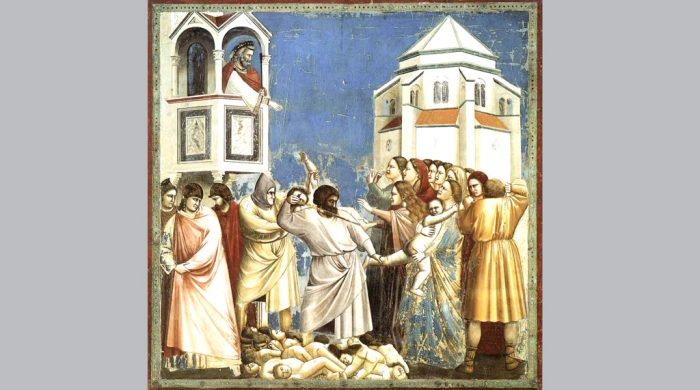

The Crusades that began in the ‘dark ages’ were holy wars par excellence. They were authorised by ‘crusading bulls’, the last of which expired only in 1940. The crusading spirit did not disappear with the expiration of the last crusading bull. Ideas, images, language, iconography, sentiments, and attitudes associated with the Crusades left a lasting influence on western civilisation and on western institutions as well. The crusading spirit guided Christopher Columbus when he ‘discovered’ the Americas. This spirit of holy war shaped the treatment of American native populations. It was mobilised against peoples of Europe as well, notably during the Enlightenment, among philosophers known for their hostility to religion.

Take Enlightenment philosophers’ reactions to a plan for perpetual peace in Europe formulated by Charles-Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre (1658–1743). Saint-Pierre proposed achieving peace in Europe through making ‘a universal crusade, incomparably more solid and better concerted than all the previous.’ European princes should settle their fights, join forces, and devote their energies to fighting back the Turk and the inroads he had made into Europe. ‘Many new Christian sovereignties’ should be established on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. Since some Ottoman domains were in Europe, this pacific ‘offensive League for the extermination of the Turks’ was holy war against non-Christian Europeans as well. Great enlightenment philosophers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Immanuel Kant questioned details of Saint Pierre’s plan, calling it a ‘peace of the graveyard’, but had no qualms about its basic logic.

The crusading spirit of Holy War shaped European colonial campaigns against non-Europeans as well. The French, for example, styled their colonisation of Algeria as King Louis-Philippe’s crusade. The crusading spirit fed into modern-day imperialism: In both Europe and the United States, World War I was presented to domestic audiences as a war to end all wars, and as a replay of the Crusades.

The great French historian of the Crusades, René Grousset, described the arrival of the French army to the Middle East as the ‘Franks’” again setting foot in Syria to ‘deliver Tripoli, Beirut, and Tyre, the city of Raymond of Saint-Gilles, the city of John of Ibelin, [and] the city of Philip der Montfort.’ Jerusalem, he went on to say, had been ‘“reoccupied” on December 9, 1917 by the descendants of King Richard under the command of Marshall Allenby.’ Like Allenby’s entry into Jerusalem, the ‘Balfour Declaration’ of 1917 can thus be regarded as a remake of the Crusades.

Holy war, just war and malicide

WHAT does the predominance of holy war in western tradition mean for peace today? To answer this, we have to turn from holy war to just war, justum bellum.

The peace that follows the end of holy war is different from the peace made at the end of just war. In theory, just war is proclaimed by a legitimate worldly authority to recover lost goods—be they real property or incorporeal rights. Just war is fought within the limits of law to redress an injury caused by the enemy. In practice, as we know from history, all kinds of crimes have been committed in wars called just, and such wars could be utterly destructive. All too often and all too easily, almost any war can be styled just. For victims of war, the fact that it might be ‘just war’ is a ‘sorry comfort’ (as Kant would say). However, just war does not erase the idea of legitimate power, law, or justice. Thus, conditions of possibility for the continued life of the beleaguered society are preserved.

In contrast to just war, holy war is righteous. As stated in the crusading epic, the Song of Roland: ‘Nos avum dreit, mais cist glutun unt tort’ (We are right, but these wretches are wrong). Holy war is unleashed in the name of a suprahuman, divine authority. It sets free willful and arbitrary violence. Holy war is freed from any respect for human laws and morality.

All wars are waged against enemies construed and represented. But holy war is fought against a universal, fundamental, existential, irreconcilable enemy. Holy War requires the construction of such an enemy. With holy war, enmity is fundamental, comprehensive, and irreconcilable. The enemy is construed as one with whom those waging holy war cannot possibly live in peace. The First Crusade constructed the Muslim as such an enemy. That image was bequeathed to future generations and lives with us today.

Holy warriors step out of the bounds of the laws of war and of law itself. They fight a fundamental, existential enemy excluded from the protection of human law. Holy warriors regard themselves as superior to their enemy; as an elect people chosen by god or divine providence; as godly people; as a higher civilisation; as a worthier race, or as an exceptional nation, Übermenschen and ‘über alles.’ When holy warriors place themselves above the norms and laws of human behavior, they strip their enemies of any kind of legal protection. Believing themselves to be authorised by a suprahuman authority, holy warriors deem their enemies subhuman and treat them with deliberate inhumanity.

Dehumanisation, the denial of humanity to the enemy, is an essential characteristic of holy war, regenerated again and again in the endless space between its beginning and end. Eradication of the enemy is but the logical conclusion of dehumanisation and a necessary element of holy war — war to the death, war to extermination. With holy war, killing the enemy is not homicide. It is malicide, the annihilation of evil.

The term malicidium was coined by Bernard of Clairvaux in the twelfth century in his praise for holy warriors. In holy wars, malicide means killing off allegedly subhuman or non-human fundamental enemies and destroying the very conditions of their existence. Not surprisingly, this usually leads to the cleansing and appropriation of land or territory. Medieval Crusaders aimed to cleanse the Holy Land of ‘infidels.’ A literary genre of the ‘recuperation’ or ‘recovery’ of the Holy Land emerged in Latin Christendom. No one seems to have been bothered by the fact that the Holy Land had never belonged to them. This logic of malicide in holy war continued through the enlightenment and onwards in a secular voice as well. And here we can now turn to examples of political discourse regarding Ukraine and Gaza.

Ukraine, Gaza and holy war

ON THE eve of World War II, German Nazis designed a plan to depopulate and de-industrialise Ukraine. They wanted to turn Ukraine into a granary for the Third Reich. After 2014, the Ukrainian government launched attacks on Russians (about a quarter of the pre-war population) to eradicate Russian language and Russian culture from Ukrainian soil. The Kiev regime and its western backers sent hundreds of thousands of men to their death, with millions fleeing the country, while western corporations, pension funds, and Saudi sovereign wealth funds took possession of this most fertile land. Not far away, meanwhile, Israeli leaders cite the Old Testament to declare that all of that land belongs to them, reducing God to their real estate agent.

The language of malicide accompanies the practice of holy war. When a black-shirted Israeli minister of defence calls Palestinians ‘human animals’, that is the language of malicide. Ukrainian language of war compared Russians to bugs, denying them the human form itself — just as the German Nazis with whom their forefathers collaborated did to the Jews. This, too, is the language of malicide. When Israeli government officials and their Euro-American allies state that Israel is fighting ‘pure evil’ in human form, they speak the language of malicide, stripping the word evil from its status as a moral category. Evil is here used as a political expedient to erase the basic coordinates of morality.

Few in the west speak of the holy war today. The language of genocide introduced in the twentieth century is more prevalent, together with a spectrum of crimes in international law: violations of the laws of war, violations of humanitarian law, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The crime of crimes since the twentieth century is genocide, which is currently aided and abetted by elites in the collective west. The genocidal record of ‘western civilisation’ has always been there to see and to study. Now, its genocidal face is live-streamed in front of our eyes. What kind of peace is possible after a postmodern live-streamed holy war?

As a fight to the end, holy war logically leads to peace of the graveyard — to harken back to the Enlightenment philosophes. In political life, unlike in texts like Saint-Pierre’s peace plan however, logic never runs smoothly. So the question we just asked — what kind of peace comes after holy war — has no preordained answer.

Political elites in the west have, expressis verbis, rejected peace. There is ample evidence that western elites in fact provoked the war in Ukraine, packaging it later as Putin’s unprovoked aggression. They dismissed Russian offers for diplomatic solution, from the Minsk Accords to December 2021 proposals for negotiation. They vetoed a ceasefire already negotiated between Ukraine and Russia in March 2022. A solution had to be found on the battlefield, the lead diplomat of the European Union continued to insist. When Pope Francis called, in March 2024, for Ukraine to immediately open peace negotiations, he was vilified by the masters of war. Ceasefire had become a proscribed word. It was banned in relation to Gaza: the US State Department issued a memo in October 2023 banning diplomats from using the word ‘ceasefire’ altogether.

With ceasefire blocked by the west, Gaza has become a modern-day Carthage, destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC. But note the difference between antiquity and our own times. Today, ‘Carthaginian peace’ does not mean total subjugation of the enemy population. The Palestinian ‘enemy population’ was subjugated long before this latest war started. Today, ‘Carthaginian peace’ means extermination. The peace pursued by the Israeli government is genocide accomplished. Ending war through genocide is not peace, it is — genocide.

Beyond the vague idea of eliminating the dehumanised enemy, neither the war in Ukraine nor the war in Gaza has a political strategy. So says the Israeli military itself. There is no political endgame, despite business plans for the ‘Day After’ in a Gaza cleansed of Palestinians and the business bonanzas in arms and farmland in a destroyed Ukraine. Mainstream media narratives meanwhile, take these wars out of their historical and political contexts. Decontextualised, they are depoliticised.

In Clausewitz’s famous phrase, war is the continuation of politics by other means. If we are unable to think about war politically, then war becomes senseless, pure violence. War becomes a substitute for politics. It becomes impossible to find a political solution to the conflict at the root of the fighting. It becomes impossible to end war and make peace. Any meaningful and sustainable peace is, necessarily, a result of politics. In the absence of politics, war can only end with total elimination of the enemy. As a political solution, peace requires finding a modus vivendi, some form of coexistence. If that is ruled out, peace can only be the peace of the graveyard. In Gaza, not even the peace of the graveyard is possible: the Israeli army has destroyed Palestinian graveyards along with everything else.

The inability to think about war politically, and liberal usage of war as a substitute for diplomacy and politics, is linked to a deeper malaise in western society: the decline of politics in general. Incompetent, corrupt, and perfidious political elites are but a symptom of that decline of politics.

Politics, in its classical definition, is about taking care of the public, common affairs of a civic community. As private economic interests assume growing control over channels of political decision making, the state as public authority is further deconstructed, and politics withers away. With the withering away of politics, war ceases to be an institution. It becomes the ‘absolute freedom and horror’ (Hegel) of destruction. In such a world, can peace be anything but the crown of destruction?

When the powerful kill with impunity and the oppressed must resort to violence in hopes of regaining a modicum of human dignity, we are all thrust inside the fragile splendor of a glass house, filled with the dark fear and cruel lust of which Augustine spoke. Our language will be the language of violence and war, coated with Orwellian propaganda of peace and democracy. If we are serious about peace, we need to relearn political language, revive politics, and radically change power relations within our societies and in our world.

Jadaliyya.com, Apr 24. Julia Elyachar is an associate professor of International and regional studies and associate professor of anthropology at Princeton University. Tomaž Mastnak is emeritus director of research at the Institute of Philosophy in the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts.