Historical lessons and their relevance today

- Update Time : Tuesday, October 22, 2024

- 20 Time View

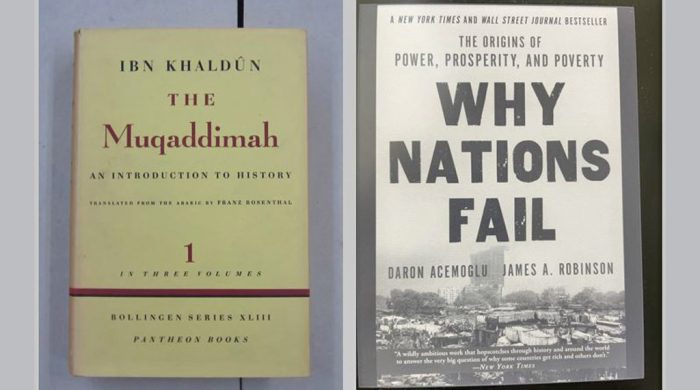

THROUGHOUT history, scholars have grappled with the question of why some nations flourish while others fall into decline. Two landmark works — Why Nations Fail (2012) by Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson, and The Muqaddimah (1377) by Ibn Khaldun — offer profound insights into this enduring question. Why Nations Fail, grounded in modern economic analysis, examines the role of political and economic institutions in determining a nation’s success. In contrast, Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah, written over six centuries ago, provides a cyclical view of societal rise and fall, focusing on social cohesion, leadership, and internal decay.

In this article, we explore the key arguments of both works, analyse the similarities between them, and investigate what their works bring to the table that is new. Finally, we apply these insights to a developing nation like Bangladesh, examining what lessons can be drawn from these theories to help guide the country’s future. The combination of historical and modern perspectives offers a rich framework for understanding how nations can navigate the challenges of development and avoid the pitfalls that have led others to failure.

How institutions shape a nation’s destiny

DARON Acemoglu and James A Robinson’s Why Nations Fail presents a thorough analysis of how different countries’ political and economic institutions determine their success or failure. The core argument of the book rests on the distinction between inclusive and extractive institutions. According to the authors, inclusive institutions are those that allow and encourage participation from a broad cross-section of society. These institutions create a level playing field and provide incentives for innovation, education, and investment, all of which contribute to sustained economic growth. Examples of countries with inclusive institutions include modern democracies like the United States and the United Kingdom, where political and economic power is distributed relatively broadly across society.

In contrast, extractive institutions concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a few. These institutions, whether political or economic, limit opportunities for the majority and stifle innovation. In such systems, the elites have little incentive to change the status quo, which allows them to exploit the resources of the nation for personal gain. Acemoglu and Robinson argue that this is why countries like North Korea, Zimbabwe, or the Congo remain poor despite having substantial natural resources.

The book provides compelling historical examples to illustrate its points. For instance, the contrast between North and South Korea demonstrates how radically different institutions in two regions with similar historical and cultural backgrounds can lead to vastly different outcomes. North Korea’s extractive institutions have led to economic stagnation and poverty, while South Korea’s inclusive institutions have allowed it to become a global economic powerhouse.

The authors also use the example of the glorious revolution in England (1688) to highlight how political changes can lead to the creation of inclusive institutions. The revolution limited the power of the monarchy and transferred significant authority to Parliament, which represented a broader section of society. This shift laid the foundation for the industrial revolution and England’s subsequent economic rise.

In essence, Why Nations Fail suggests that long-term prosperity is closely tied to the inclusiveness of a nation’s institutions. Nations that fail to develop inclusive institutions remain trapped in cycles of exploitation and poverty, while those that embrace inclusivity unlock the potential for sustainable growth.

Timeless wisdom of Ibn Khaldun

LONG before modern economics and political science emerged as fields of study, Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century historian, sociologist, and philosopher, provided a profound analysis of how civilisations rise and fall. In his monumental work, The Muqaddimah Ibn, Khaldun laid the groundwork for what can be seen as an early theory of social and economic development.

At the heart of Ibn Khaldun’s theory is the concept of ‘asabiyyah’, or social cohesion. He argues that the strength of a society is directly tied to its level of social solidarity and unity. Societies with strong ‘asabiyyah’ — often found in nomadic or tribal communities — can work together effectively, creating a sense of shared purpose and mutual trust. This unity allows them to conquer other societies and establish powerful dynasties or states.

However, according to Ibn Khaldun, as these societies become more prosperous, they also become more sedentary and urbanized. Over time, the strong social bonds that once united them weaken due to increased wealth, luxury, and moral decay. Leaders and elites become corrupt, focusing more on personal gain than the well-being of the broader community. As social cohesion erodes, society becomes vulnerable to both internal strife and external invasion, ultimately leading to its decline and fall.

Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical theory of civilisation is evident in his analysis of the rise and fall of empires throughout history, particularly in the Muslim world. For example, he used this framework to explain the decline of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, both of which initially rose to power through strong ‘asabiyyah’ but later fell due to corruption and the weakening of social bonds.

The parallels between Ibn Khaldun’s analysis and modern theories of economic and political development are striking. His focus on the role of leadership, social unity, and internal decay in determining the success or failure of a civilisation provides a timeless framework for understanding why societies prosper or collapse.

Parallels across time: comparing two theories

WHILE Why Nations Fail and Muqaddimah were written centuries apart and reflect the intellectual traditions of their respective times, there are several key similarities in their analysis of societal success and failure.

Internal factors and leadership: Both works emphasise the importance of internal factors in determining the rise or fall of nations. Ibn Khaldun focuses on the role of leadership and the erosion of social cohesion, while Acemoglu and Robinson highlight the central role of political and economic institutions. In both cases, it is the structure and quality of governance that determine whether a society thrives or collapses.

The role of elites: Both Ibn Khaldun and the authors of Why Nations Fail are critical of elites who exploit their positions for personal gain. Ibn Khaldun describes how leaders become corrupt over time, focusing on luxury and personal wealth rather than the needs of the community. Similarly, Acemoglu and Robinson argue that extractive institutions allow elites to concentrate power and wealth, which stifles innovation and leads to economic stagnation.

Cycles of prosperity and decline: Ibn Khaldun’s cyclical view of history, where societies rise through strong social cohesion but later fall due to corruption and luxury, echoes the idea in Why Nations Fail that nations often transition from inclusive to extractive institutions. The weakening of inclusive structures, whether through internal decay or external forces, leads to long-term decline.

Moral and ethical decay: Both works recognise the role of moral and ethical decay in the downfall of civilisations. Ibn Khaldun writes about the moral decay that accompanies luxury and prosperity, weakening a society’s internal unity. Acemoglu and Robinson similarly argue that when institutions become extractive, corruption and moral decay set in, preventing long-term growth.

Despite these similarities, there are also important differences between the two frameworks, particularly in the specificity and scope of the institutional analysis provided in Why Nations Fail.

Insights from ‘Why Nations Fail’

While Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah provides a profound framework for understanding the rise and fall of civilisations, Why Nations Fail introduces several new dimensions to the discussion, particularly through its focus on institutions and its application to the modern world.

Institutional Framework: The most significant contribution of Why Nations Fail is its detailed analysis of how specific institutions — political, economic, and legal — shape the trajectory of nations. Acemoglu and Robinson move beyond general factors like leadership or social cohesion to examine how the structure of institutions either promotes inclusivity or perpetuates extraction. This institutional framework provides a clearer roadmap for understanding why certain nations succeed while others fail, offering policymakers actionable insights.

Global examples and historical breadth: While Ibn Khaldun focused primarily on the Arab-Muslim world, Why Nations Fail draws on a much broader array of historical and global examples. From the colonisation of the Americas to the rise of industrial England, the book provides a diverse range of case studies that illustrate how institutional differences shape economic outcomes across different eras and regions.

Modern economic theories: Acemoglu and Robinson also incorporate modern economic theories, such as creative destruction and innovation, into their analysis. They argue that inclusive institutions not only protect property rights and encourage investment but also foster an environment where new ideas can flourish. This is a concept that was less developed in Ibn Khaldun’s framework, which focused more on the social and political aspects of civilisation.

Empirical evidence: Why Nations Fail builds on a wealth of empirical research, using historical data to test and support its claims. This scientific approach, which includes statistical analysis and detailed historical comparisons, adds a level of rigour to the theory that was not available in Ibn Khaldun’s time.

Lessons for Bangladesh’s path to prosperity

FOR a developing nation like Bangladesh, the lessons drawn from both Why Nations Fail and Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah offer crucial insights into building a stable and prosperous future. As we have seen, the rise and fall of nations depend largely on the strength of their institutions, the quality of governance, and the degree of social cohesion. These are areas where Bangladesh can shape its trajectory.

First, inclusive institutions are key. Why Nations Fail demonstrates that nations thrive when political and economic power is distributed broadly, allowing for innovation and equal opportunities. For Bangladesh, fostering democratic values, enhancing the rule of law, and addressing systemic corruption are necessary steps toward creating an inclusive society. This means strengthening institutions that empower all citizens rather than concentrating power in the hands of a few elites. As Bangladesh continues to grow economically, the focus must shift toward reducing inequality and ensuring that all segments of society benefit from development.

Second, Ibn Khaldun’s concept of ‘asabiyyah—social cohesion—highlights the importance of unity in driving a society forward. Bangladesh must work to overcome political and/or religious divisions and ensure that national interests take precedence over partisan gains. Unity is the bedrock of sustained progress, and only by maintaining strong social bonds can the nation avoid the internal strife that Ibn Khaldun warned about.

Finally, both frameworks underscore the danger of corruption and moral decay. Bangladesh’s long-term success will depend on its ability to combat these threats through transparency and good governance. Corruption not only erodes public trust but also hampers economic progress by diverting resources away from productive use.

By learning from the successes and failures of other nations, Bangladesh can chart a path that avoids the pitfalls of extractive institutions and societal fragmentation. The combination of inclusive governance, social unity, and ethical leadership can serve as the foundation for a prosperous and equitable future for the country.

Conclusion

IN ANALYSING the rise and fall of nations through both the modern lens of Why Nations Fail and the classical insights from Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah, we gain a comprehensive understanding of how institutions, governance, and social cohesion dictate the success or failure of societies. Both perspectives, though originating centuries apart, highlight that the internal dynamics of a nation — its political systems, economic policies, and social structures — are crucial to its ability to prosper.

As we have seen, extractive institutions that centralise power and wealth within a narrow elite lead nations down the path of stagnation and eventual collapse. On the other hand, inclusive institutions that empower citizens, encourage innovation, and distribute resources equitably lay the groundwork for long-term success. Ibn Khaldun’s focus on social cohesion further emphasises that a nation’s strength is not just in its laws but in its ability to unite its people under a common purpose.

For a developing country like Bangladesh, these lessons are not merely theoretical; they offer a roadmap for addressing the nation’s current challenges. By fostering inclusive institutions, strengthening the rule of law, and maintaining social unity, Bangladesh can score out a prosperous and stable future. However, corruption and political division remain significant threats, as both Why Nations Fail and Muqaddimah remind us that internal decay can derail progress.

In conclusion, the synthesis of these two monumental works provides a powerful framework for understanding not only the successes and failures of past civilisations but also the potential pathways forward for nations like Bangladesh. By learning from history and applying these insights thoughtfully, Bangladesh can avoid the traps that have held back other nations and create a future that is both equitable and prosperous for all its citizens.

M Riazul Islam is an associate professor of the University of Aberdeen, UK.