Coronavirus: What does Covid-19 do to the brain?

- Update Time : Wednesday, July 1, 2020

- 183 Time View

Stroke, delirium, anxiety, confusion, fatigue – the list goes on. If you think Covid-19 is just a respiratory disease, think again.

As each week passes, it is becoming increasingly clear that coronavirus can trigger a huge range of neurological problems.

Several people who’ve contacted me after comparatively mild illness have spoken of the lingering cognitive impact of the disease – problems with their memory, tiredness, staying focused.

But it’s at the more severe end that there is most concern.

Chatting to Paul Mylrea, it’s hard to imagine that he had two massive strokes, both caused by coronavirus infection.

The 64-year-old, who is director of communications at Cambridge University, is eloquent and, despite some lingering weakness on his right side, able-bodied.

He has made one of the most remarkable recoveries ever seen by doctors at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN) in London.

His first stroke happened while he was in intensive care at University College Hospital. Potentially deadly blood clots were also found in his lungs and legs, so he was put on powerful blood-thinning (anticoagulant) drugs.

A couple of days later he suffered a second, even bigger stroke and was immediately transferred to the NHNN in Queen Square.

Consultant neurologist Dr Arvind Chandratheva was just leaving hospital when the ambulance arrived.

“Paul had a blank expression on his face,” he says. “He could only see on one side and he couldn’t figure out how to use his phone or remember his passcode.

“I immediately thought that the blood thinners had caused a bleed in the brain, but what we saw was so strange and different.”

Paul had suffered another acute stroke due to a clot, depriving vital areas of the brain of blood supply.

Tests showed that he had astonishingly high levels of a marker for the amount of clotting in the blood known as D-dimer.

Normally these are less than 300, and in stroke patients can rise to 1,000. Paul Mylrea’s levels were over 80,000.

“I’ve never seen that level of clotting before – something about his body’s response to the infection had caused his blood to become incredibly sticky,” says Dr Chandratheva.

During lockdown there was a fall in the number of emergency stroke admissions. But in the space of two weeks, neurologists at the NHNN treated six Covid patients who’d had major strokes. These were not linked to the usual risk factors for stroke such as high blood pressure or diabetes. In each case they saw very high levels of clotting.

Part of the trigger for the strokes was a massive overreaction by the immune system which causes inflammation in the body and brain.

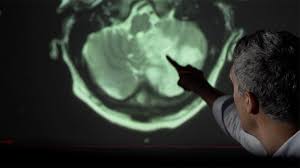

Dr Chandratheva projected Paul’s brain images on a wall, highlighting the large areas of damage, shown as white blurs, affecting his vision, memory, coordination, and speech.

The stroke was so big that doctors thought it likely he would not survive, or be left hugely disabled.

“After my second stroke, my wife and daughters thought that was it, they would never see me again,” Paul says. “The doctors told them there was not much they could do except wait. Then I somehow survived and have been getting progressively stronger.”

One of the first encouraging signs was Paul’s ability with languages – he speaks six – and he would switch from English to Portuguese to speak to one of his nurses.

“Unusually he learned several of his languages as an adult, and this will have created different wiring connections in the brain which have survived his stroke,” says Dr Chandratheva.

Paul says he cannot read as fast as he used to, and is sometimes forgetful, but that’s hardly surprising given the areas of damage in his brain.

His physical recovery has also been impressive, which doctors attribute to his previous very high level of fitness.

“I used to cycle for an hour a day, do a couple of gym sessions a week and swim in the river. My cycling and diving days are over, but I hope to get back to swimming,” Paul says.

A study in the Lancet Psychiatry found brain complications in 125 seriously ill coronavirus patients in UK hospitals. Nearly half had suffered a stroke due to a blood clot while others had brain inflammation, psychosis, or dementia-like symptoms.

One of the report authors, Prof Tom Solomon of the University of Liverpool, told me, “It’s clear now that this virus does cause problems in the brain whereas initially we thought it was all about the lungs. Part of it is due to lack of oxygen to the brain. But there appear to be many other factors, such as problems with blood clotting and a hyper-inflammatory response of the immune system. We should also ask whether the virus itself is infecting the brain.”

In Canada, neuroscientist Prof Adrian Owen has launched a global online study of how the virus affects cognition. Owen said: “We already know that ICU survivors are vulnerable to cognitive impairment. So as the number of recovered Covid-19 patients continues to climb, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that getting sent home from the ICU is not the end for these people. It’s just the beginning of their recovery.”

“Sars and Mers, which are both caused by coronaviruses, were associated with some neurological disease, but we’ve never seen anything like this before,” Dr Michael Zandi, consultant neurologist at the NHNN, told me. “The closest comparison is the 1918 flu pandemic. We saw then there was a lot of brain disease and problems that emerged over the next 10-20 years.”

As the BBC’s medical correspondent, since 2004 I have reported on global disease threats such as bird flu, swine flu, Sars and Mers – both coronaviruses – and Ebola. I’ve been waiting much of my career for a global pandemic, and yet when Covid-19 came along, the world was not as ready as it could have been. Sadly, we may have to live with coronavirus indefinitely. Here, I will be reflecting on that new reality.

A mysterious neurological syndrome known as encephalitis lethargica appeared around the end of World War One and went on to affect more than a million people worldwide. There is limited evidence of its causes, and whether the trigger was influenza or a post-infectious autoimmune disorder.

As well as a sleepiness coma, some patients had movement disorders that looked like Parkinson’s disease, which affected them for the rest of their lives.

In his book Awakenings, the neurologist Oliver Sacks told the story of a group of patients who’d been frozen in sleep for decades, and how he used the drug L-Dopa to temporarily free them from their locked-in state.

We should be careful before reading too much into comparisons between Covid-19 and the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. But with so many Covid patients having neurological symptoms, it will be important to look at the long-term effects on the brain.