India coronavirus: Online classes expose extent of digital divide

- Update Time : Thursday, July 23, 2020

- 199 Time View

Mahima and Ananya are in the same class at a small private school in the northern Indian state of Punjab.

Teachers describe them both as “brilliant” students, but ever since classes moved online, they have found themselves on opposite sides of India’s digital divide.

Ananya, who lives in an urban area, has wi-fi at home, and says she is able to log in to her classes and follow them easily.

“The experience is awesome and classes are going really well. This is our school now,” she told BBC Punjabi.

But for Mahima, who lives in a village, it has been a frustrating experience.

For one, she has no home wi-fi. Instead she relies on her mobile phone’s 4G signal, a common source of internet across rural and small-town India.

But the phone signal is strongest on the terrace of her house, so Mahima often has no choice but to study there in the searing heat. Even then, she says, she may or may not be able to join the classes online.

“At times I miss lessons completely. I can’t watch online videos sent by the teacher. Downloading is a big problem. We only get electricity a few hours a day, so keeping the phone charged is also an issue,” she says.

“I have barely attended 10-12 classes in the last one and half months. At times I feel like crying because of the backlog. I am so behind the syllabus.”

The government has been touting online classes as a viable alternative, but unequal and patchy access to the internet has meant the experience is vastly different depending on location and household income.

With more than 630 million subscribers, India is home to the world’s second-largest internet user base. But connectivity is still an issue, especially since mobile data – rather than wi-fi – is the main source.

The signal is often uneven, making it hard to stream videos smoothly, and electricity supply is erratic, which means devices often run out of charge.

All of this was recently flagged by state representatives to the federal ministry of human resource development, which oversees education in India.

The Indian Express newspaper quoted senior officials warning that almost 30% of the central state of Jharkhand had poor connectivity, while similar complaints had been made in Arunachal Pradesh in the north-east.

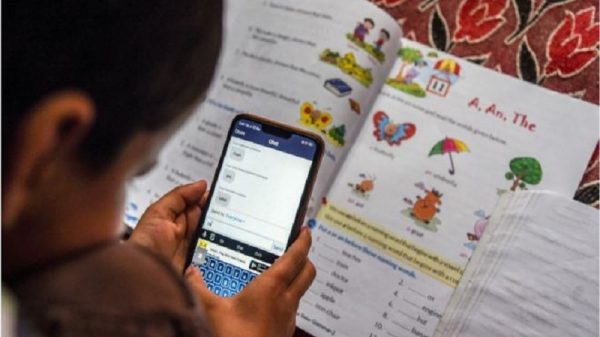

There are other issues too. The internet device most Indians use is a mobile phone – so many students follow classes on cheap phones rather than laptops. Many poor households have only one phone, and access to it is unreliable.

And then there are those who can’t afford any device at all.

In the southern state of Kerala, for instance, a teenager killed herself, allegedly because her family could not afford a mobile phone or a television (lessons are being aired on a special educational channel).

Her father told local journalists that he was a daily-wage earner and could not afford either.

“She was very worried that she would not be able to attend the classes. I had told her that some solution will be found by the teachers, but she was very upset,” he said.

Smriti Parsheera, a lawyer and technology policy researcher, told the BBC: “As everyone was unexpectedly thrust into an online-only environment, the type and number of devices that a family had became instrumental in deciding a student’s ability to engage with the system.

“At one extreme of this spectrum are those who do not have any type of device and therefore get completely excluded. Many students in government-run schools have faced this problem.

It’s not just about whether you can access the internet, she says – it’s how you do it too.

“There is a clear difference in the user experience of doing online classes on a mobile phone versus a computer or a laptop.”

State governments and civil associations have tried to address this.

The death of the student in Kerala compelled two rival student organisations to work together to provide television sets to students.

“In some houses, particularly in tribal communities, we are getting electrical connections established,” one representative told BBC Hindi.