How tourism, gentrification and a pandemic have changed Asia’s street food scene

- Update Time : Wednesday, December 23, 2020

- 179 Time View

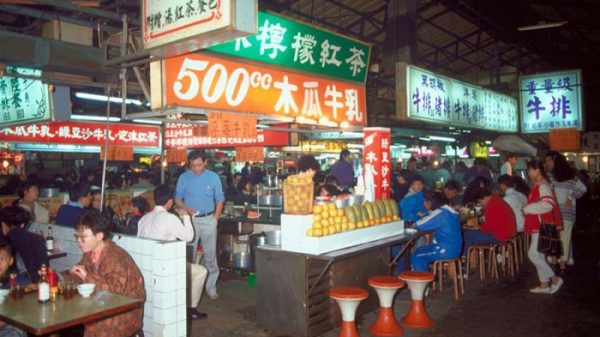

A decade ago, Shilin Night Market was one of the hottest night markets in Taipei, packed to the brim with vendors slinging out hot bites of stinky tofu, barbecue squid and copious amounts of grilled meats on skewers.

Taipei culture writer Jason Cheung, who has been meticulously documenting the night market’s history on his blog, is convinced those days are long gone.

“It used to be so packed, you could barely move your arms,” he says, walking down an alley flanked by food vendors on both sides, his arms outstretched. Today — on a Friday night — the market is at less than half its usual capacity.

Even though Taiwan surpassed 250 consecutive days without a locally transmitted case of Covid-19, the problem is that markets like Shilin have been too dependent on international tourists.

“Before Shilin was so diverse,” he says of the food options. “This market is now all about tourism. Everyone sells the same things. It’s boring.”

Taiwan is considered synonymous with night markets — an informal congregation of peddlers that once upon a time relied on the magnetism of temples.

A tradition carried over from dynastic China, people would congregate at temples on a regular basis. Opportunistic vendors would swarm in from all directions to sell their wares on shoulder poles or simple push carts.

It’s here where the perception of night markets has been stuck in time — dense, bright lanes packed with people, where vendors are one-dish specialists, perfecting the same food for generations.

In the latter part of the 20th century, a period of economic prosperity — often called the Taiwan Miracle — created a boom for businesses across the island.

“From a business perspective, night markets were at their most prosperous in the 80s and up until the mid-90s,” says Dr. Shuenn-Der Yu, a faculty member at the Academia Sinica Institute of Ethnology, whose doctoral thesis focused on Taiwanese night markets.

However, hygiene and construction standards weren’t always up to par, and the proliferation of diseases like malaria along with fire safety concerns prompted authorities to relocate and reconstruct night markets multiple times throughout their histories.

At Shilin Night Market, for instance, a bright, underground section was added in 2011 in an attempt to contain many of the food vendors and tidy up the street.

The project flopped. Today, while there are still a healthy number of above ground vendors that are doing well, the underground section is the least trafficked part of the night market — despite ample lighting and air conditioning.

“A lot of people grew up around here, so when the market moved underground, many people couldn’t accept it. It’s like a mall underground street,” says Cheung, pointing out that all the menus are nearly identical in style and content.

“Carnivals controlled by the establishment”

Shilin Night Market is but a microcosm for a lot of night markets across the island, where attempts to micromanage have largely fallen flat.

“In 1998, the government also proposed a five-year project to gentrify morning and night markets across the island,” wrote Yu in a 2004 book about Taiwanese culture.

These initiatives introduced elements like uniforms, performances and trade shows.

“[Many] night markets may become carnivals controlled by the establishment for the people,” he speculated. “If this trend continues, the days of the truly hot and noisy night market may soon be a thing of the past.”

Kathy Cheng, a culture writer and communications consultant in Taipei, agrees.

“Night markets are stagnant overall,” she says. “The famous stalls are still great, but they are holding up the standard and carrying the legacy. It doesn’t feel like people at the government level are really thinking about how to protect, preserve and evolve for the future.”

Of course, not all Taipei night markets have suffered the same fate as Shilin.

Ningxia Night Market, Cheng points out, is one of the few markets in Taipei that has retained its allure.

“The standard types of Taiwanese food are still all there — oyster omelette, coal-grilled sausages, fried chicken, pig’s blood cake, stinky tofu — and the way the night markets look and operate is more or less the same too,” she says.

In some form or another, traditional street food will always be around, but the problem, say locals, is that the markets are becoming more homogenous.

“I think the quality is pretty much the same. But the diversity of food options has gone down,” says Cheung. “When you go to Taiwan’s old streets, you’ll see that the food is repetitive. They are duplicates of one another.

According to Yu, successful night market businesses specializing in one dish — like salt and pepper chicken or braised duck head — began to franchise out their businesses beginning in the 1990s.

Food could be made in a central kitchen and then distributed to the stall owners to heat up on site.

“Some people want to enter the night market but they don’t know how to cook,” Yu says. “So they sign up to be a franchisee and all they have to do is fry the chicken.”

“Now a lot of things that are sold are the same,” he adds. “It’s a cause for concern.”

Preserving the culture — and chaos of street food

The erosion of street food culture is not unique to Taipei; it’s unfolding all throughout Asia.

The very definition of street food is food sold on the streets, and, for centuries, it was the apex of economic activity in cities and a way for low-income urban street vendors to provide goods at low prices.

But with development has come a higher standard for hygiene and order — forces contradicting the spontaneous nature of night markets. Meanwhile, globalization introduced dishes from all over the world and competition from multinational restaurant chains.

In the last few decades, cities all over Asia have been struggling with how to preserve the cultural importance of street food — all while containing its inherent chaos.

In Beijing, this containment has led to the eradication of virtually all spontaneous street food stalls and markets. The shopping street of Wangfujing — once home to a bustling night market, is now a wide pedestrian boulevard flanked by large department stores.

In Tokyo, street food alleys are being infiltrated by chain stores.

“The media often portrays street food in Tokyo as those yakitori stands underneath the train tracks in central Tokyo,” says Japan-based food writer Melinda Joe.

“Those kinds of places have been undergoing renovation in the last two years. It’s both good and bad. A lot of those yakitori restaurants were really not that good. But those places are also now getting slowly replaced by a lot of chains. There’s a big Starbucks there.”

In Hong Kong, street food has an actual expiration date. There are only 25 licensed street vendors left — called dai pai dongs — and the government isn’t issuing new licenses.

“The license follows the business owner, not the business,” explains Hong Kong food writer Janice Leung Hayes.

“If the business owner passes away or decides to retire, they can’t pass the business onto someone else. When their license is over, their stall has to close.”

Over the past decade in South Korea, authorities have been cracking down on unlicensed vendors.

According to the Korea Times, in 2017, 7,300 people were running street stalls in the Seoul, yet only 1,000 among them had city permission.

“Street food was always kind of a legal grey area from what I understand, but they really started to crack down,” says Robert Joe, a Korean-American filmmaker based in Seoul.