Did nuclear spy devices in the Himalayas trigger India floods?

- Update Time : Monday, February 22, 2021

- 203 Time View

In a village in the Indian Himalayas, generations of residents have believed that nuclear devices lie buried under the snow and rocks in the towering mountains above.

So when Raini got hit by a huge flood earlier in February, villagers panicked and rumours flew that the devices had “exploded” and triggered the deluge. In reality, scientists believe, a piece of broken glacier was responsible for the flooding in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, in which more than 50 people have died.

But tell that to the people of Raini – the farming mountain village with 250 households – and many don’t quite believe you. “We think that the devices could have played a role. How can a glacier simply break off in winter? We think the government should investigate and find the devices,” Sangram Singh Rawat, the headman of Raini, told me.

At the heart of their fears is an intriguing tale of high-altitude espionage, involving some of the world’s top climbers, radioactive material to run electronic spy systems, and spooks.

It is a story about how the US collaborated with India in the 1960s to place nuclear-powered monitoring devices across the Himalayas to spy on Chinese nuclear tests and missile firings. China had detonated its first nuclear device in 1964.

“Cold War paranoia was at its height. No plan was too outlandish, no investment too great and no means unjustified,” notes Pete Takeda, a contributing editor at US’s Rock and Ice Magazine, who has written extensively on the subject.

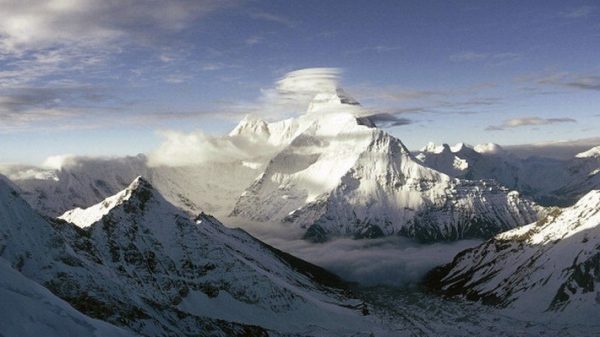

In October 1965, a group of Indian and American climbers lugged up seven plutonium capsules along with surveillance equipment – weighing some 57kgs (125 pounds) – which were meant to be placed on top of the 7,816-metre (25,643-ft) Nanda Devi, India’s second highest peak, and near India’s north-eastern border with China.

A blizzard forced the climbers to abandon the climb well short of the peak. As they scampered down, they left behind the devices – a six-foot-long antenna, two radio communication sets, a power pack, and the plutonium capsules – on a “platform”.

One magazine reported that they were left in a “sheltered cranny” on a mountainside which was sheltered by the wind. “We had to come down. Otherwise many climbers would have been killed,” Manmohan Singh Kohli, a celebrated climber who worked for the main border patrol organisation and led the Indian team, said.

When the climbers returned to the mountain next spring to look for the device and haul it back to the peak, they had vanished.

More than half a century later and after a number of hunting expeditions to Nanda Devi, nobody knows what happened to the capsules.

“To this day, the lost plutonium likely lies in a glacier, perhaps being pulverised to dust, creeping towards the headwaters of the Ganges,” wrote Mr Takeda.

This could well be an exaggeration, say scientists. Plutonium is the main ingredient of an atomic bomb. But plutonium batteries use a different isotope (a variant of a chemical element) called plutonium-238, which has a half-life (the amount of time taken for one-half of a radioactive isotope to decay) of 88 years.

What survives are the stories of a fascinating expedition.

In his book Nanda Devi: A Journey to the Last Sanctuary, British travel writer Hugh Thompson recounts how the American climbers were asked to use an Indian sun tan lotion to darken their skins so that they didn’t evoke suspicion among locals; and how the climbers were told to pretend that they were on a “high altitude programme” to study the effects of low oxygen on their bodies. The porters who carried up the nuclear luggage were told it was a “treasure of some sort, possibly gold”.

Before that, the climbers, reported Outside, an American magazine, were taken to Harvey Point, a CIA base in North Carolina, for a crash course in “nuclear espionage”. There, a climber told the magazine, that “after a while, we spent most of our time playing volleyball and doing some serious drinking”.

The botched expedition was kept a secret in India until 1978, when the Washington Post picked up the story reported by Outside, and wrote that the CIA had hired American climbers, including members of a successful recent summit of Mount Everest, to place nuclear-powered devices on two peaks of the Himalayas to spy on the Chinese.

The newspaper confirmed that the first expedition ended in the loss of the instrument in 1965, and the “second foray happened two years later and ended in what one former CIA official termed a “partial success”.

In 1967, a third attempt to plant a fresh set of devices, this time on an adjacent and easier 6,861-metre (22,510-ft) mountain called Nanda Kot, had succeeded. A total of 14 American climbers, had been paid $1,000 a month for their work to put the spying devices in the Himalayas over three years.

In April 1978, India’s then prime minister Morarji Desai dropped a “bombshell” in the parliament when he disclosed that India and the US had collaborated at “top level” to plant these nuclear-powered devices on the Nanda Devi. But Desai did not say how far the mission was successful, according to a report.

Declassified US State Department cables from the same month talk about some 60 people demonstrating outside the embassy in Delhi against “alleged CIA activities in India”. The protesters carried signs, saying “CIA Quit India” and “CIA is poisoning our waters”.

As for the lost nuclear devices in the Himalayas, nobody quite knows what happened to them. “Yeah, the device got avalanched and stuck in the glacier and God knows what effects that will have,” Jim McCarthy, one of the American climbers, told Mr Takeda.

Climbers say a small station in Raini regularly tested the waters and sand from the river for radioactivity, but it is unclear whether they got any evidence of contamination.

“Until the plutonium [the source of the radio-activity in the power pack] deteriorates, which may take centuries, the device will remain a radioactive menace that could leak into the Himalayan snow and infiltrate the Indian river system through the headwaters of the Ganges,” Outside had reported.

I asked Captain Kohli, now 89, whether he regretted being part of an expedition which ended up leaving nuclear devices in the Himalayas

“There is no regret or happiness. I was just following orders,” he said.