Who is the hero? Albright v Assange

- Update Time : Saturday, April 30, 2022

- 114 Time View

Lawrence Davidson checks on the answer, from inside and outside the establishment

OUR image of a hero has two aspects. The first consists of generic, stereotypical traits: bravery, determination in the face of adversity, achievement against heavy odds — the kind of person who saves the day.

The second aspect is more culturally specific, describing and contextualizing the circumstances of bravery and determination, and the nature of achievement in terms that are narrowly defined. In other words, cultural descriptions of bravery are most often expressed in terms compatible with the social and political conditions of the hero’s society.

Heroes are ubiquitous. For instance, there are American heroes, Russian heroes, Israeli heroes, Arab heroes, Ukrainian heroes, and so on. Where does good and bad come into it? Well, that too becomes a cultural judgment. Below are two examples of ‘heroes.’ I will leave it to the reader to decide who is good and who is bad.

Albright: from outside establishment

MADELEINE Albright was the first woman to serve as American secretary of state (1997–2001). She served in this capacity under president Bill Clinton during his second term.

As such, she must be seen as a loyal promoter of her president’s foreign policy — a policy she may have helped create — regardless of any moral or ethical considerations. In other words, she is a ‘company’ point person.

Whether this requires bravery is questionable. As we will see, it will require a persistence toward a single end defined in societal or national terms. This does indicate determination and achievement in the face of an alleged foe.

When Madeleine Albright died in 2022, the following ‘achievements’ were critically cited in the obituaries written by those outside the establishment and thus critical of Albright:

— Russia was ‘her obsession’ and this led to her being the US government’s point person on the expansion of NATO eastward into what had been the Soviet sphere of influence. This was done in violation of guarantees given to Russia in 1989 that NATO would not go further than the border of the newly united Germany — an act that helped prepare the ground for the present war in Ukraine.

— In 1997–1998, acting as secretary of state, she threatened Iraq with aerial bombardment if its government did not allow for weapons inspections at designated sites. The Iraqis eventually complied but got bombed anyway.

— She also made sure draconian sanctions were applied (including banning many medicines) to Iraq for an extended period of time. The result was the death of hundreds of thousands of civilians, including 500,000 Iraqi children. When asked by the journalist Lesley Stahl on the TV show 60 Minutes whether the draconian sanctions were worth the price of the deaths of approximately a half-million Iraqi children, she replied, ‘we think this was a very hard choice, but the price — we think the price is worth it.’

This led one critic of the US government to judge Albright’s career as follows:

‘It is the ultimate moral crime to target for misery, pain and death those least responsible for the offenses of their tyrannical rulers. Yet this is the very policy Madeleine Albright, made ‘Standard Operating Procedure for US diplomacy.’

Albright: from inside establishment

FROM inside the establishment, that is, from inside the US government and foreign policy establishment as well as an allied media, she was lauded as a dedicated, talented and energetic leader.

One member of the House of Representatives said upon her death, ‘Our nation lost a hero today. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was the face of US foreign policy throughout some of the most difficult times for our nation and the world…. She brought nations together to expand NATO and defend the very pillars of democracy across the world…. She taught us that we can solve some of the world’s most difficult issues by bringing people together and having tough, uncomfortable conversations.’

According to the eulogistic obituary published by The New York Times, ‘Her performance as secretary of state won high marks from career diplomats abroad and ordinary Americans at home. Admirers said she had a star quality, radiating practicality, versatility and a refreshingly cosmopolitan flair.’

What can we conclude from these contrasting views? We quickly come to realize that inside the establishment one rarely, if ever, hears any reference to such things as the human cost of a policy, the end of which is defined in terms of national interest. In the case of Madelene Albright, national interest trumped human interest. Still, she was held a hero nonetheless.

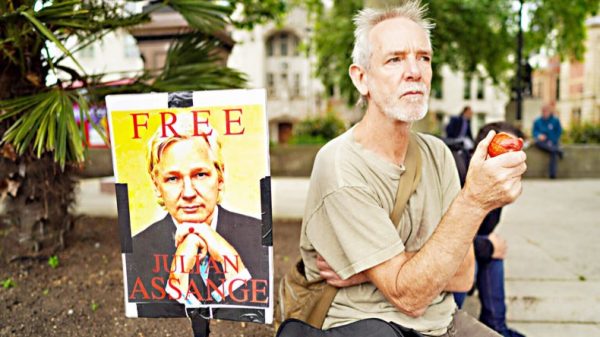

Assange & Manning

JULIAN Assange is an Australian computer specialist who founded WikiLeaks in 2006. It is a web site dedicated to providing ‘primary source materials’ to journalists and the public alike.

WikiLeaks eventually released ‘thousands of internal or classified documents from an assortment of government and business entities.’ The site raised immediate hostility from many governments and corporations, which decried the ‘lack of ethics’ of Assange and his fellows — who were exposing the often unethical, and sometimes murderous, behavior of those now attacking the web site.

Bradley (aka Chelsea) Manning was an Army intelligence specialist assigned to a base near Baghdad during the Iraq War. Manning was suffering from a gender identity crisis. He also had serious second thoughts about the Iraq war.

Eventually, his growing opposition to the war led him to secretly send Assange ‘750,000 classified, or unclassified but sensitive, military and diplomatic documents.’ Manning was later exposed and arrested, court-martialled and eventually had his sentence commuted by president Barack Obama.

From inside establishment

AS THE writer and therapist Steven Berglas observes, ‘for as long as there have been moral canaries in our societal coal mines they have been denigrated for being as corrupt, or more so, than the miscreants they attack.’

Assange and Manning face just such charges.

The complaints were, if you will, weaponized in 2010 after

WikiLeaks released ‘half a million documents’ relating to US actions in Iraq and Afghanistan, obtained from the then young, disillusioned Army intelligence analyst Manning.

This was followed by another release of about a quarter-million U.S. diplomatic cables, many of which were classified.

Assange was now deemed ‘a terrorist’ by the government terrorists he had exposed. Subsequently, these actions were deemed ‘a threat to US national security’ by the US government.

As a result, Manning was jailed and suffered court-martial while Assange, now living in England, has been fighting extradition to the US for years.

From inside the establishment both Assange and Manning are criminals. Both exposed secrets of governments and it is an established principle that states cannot run without secrets. This is partially because all states sometimes act in criminal ways. To expose these episodes is deemed more criminal than criminal acts of the states. Why so? Because governments say so and design their laws accordingly.

This rather arbitrary position taken by governments has been sold to the citizenry as necessary for the security of their state, but as we see, the consequences of WikiLeaks’mass release of classified documents has not been shown to have endangered the nation in any obvious way. Nonetheless, Assange and Manning are deemed criminals for setting a precedent that threatens other potential criminals employed by state and business.

From outside establishment

OUTSIDE the establishment the view is 180 degrees in the other direction. Again, to quote Steven Berglas: ‘whistleblowers are rare, courageous birds that should be considered national treasures not disgraces.… It is clear that most snitches have more integrity — and are infinitely more altruistic-than their government or corporate counterparts.’

For instance, according to journalist Glenn Greenwald, Manning is ‘a consummate hero, and deserves a medal and our collective gratitude, not decades in prison.’

At court-martial, Manning stated that the leaked material to WikiLeaks was intended to ‘spark a domestic debate of the role of the military and foreign policy in general… and cause society to reevaluate the need and even desire to engage in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations that ignore their effect on people who live in that environment every day.’

A heroic act, but also perhaps a naive one.

Issue of ethics

GOVERNMENTAL leaders and their aides often reserve for themselves the right to do illegal things such as

— using sanctions that undermine opposition governments while ignoring the negative consequences on the wellbeing of civilian populations;

— aiding and abetting coups that overthrow democratic and undemocratic governments alike, depending on how, in each case, Washington sees their economic and military stance; and

— carrying out of illegal actions such as assassination, torture, and illegal imprisonment. All of this is immoral and unethical while being deemed necessary within the context of national interest.

Nonetheless the common citizen, who lives within what we shall call a propaganda bubble spun by his/her own government and its cooperating mainstream media, has a hard time understanding events except in propaganda designed terms.

Most will pay no attention at all to the fate of whistleblowers, who speak in opposition to the propaganda, because their actions do not touch their lives, which are locally focused. For the small number who find that there is something not quite right about negative media reports of whistleblower revelation, there is often a sense of helplessness and inertia that causes their momentary uneasiness to go nowhere.

The unfortunate truth is that this phenomenon of mass indifference to what the government does in the name of national interest and security, backed up by seemingly blind support of the media, has become one of the pillars of societal stability.

That does not mean that challenges such as those launched by Assange and Manning are not worth the effort. They might lead to reforms (the Watergate scandal and its consequences comes to mind), but under ordinary circumstances the status quo will carry on.

So, who are the heroes? Is it those who promote state policies which, regardless of their immorality, allegedly sustain state prestige, security and stability? Or is it those who shine a momentary light into dark places and reveal the immorality of state behavior — often at the cost of the destruction of their careers and reputations? You choose.

Consortiumnews.com, April 28. Lawrence Davidson is professor of history emeritus at West Chester University in Pennsylvania.