The new cold war heats up Asia

- Update Time : Wednesday, October 19, 2022

- 114 Time View

IF THE world is indeed entering a new Cold War, it bears little resemblance to the final years of that global conflict with its frequent summits between smiling leaders and its arms agreements aimed at de-escalating nuclear tensions. Instead, the world today seems more like the perilous first decade of that old Cold War, marked by bloody regional conflicts, threats of nuclear strikes, and the constant risk of superpower confrontation.

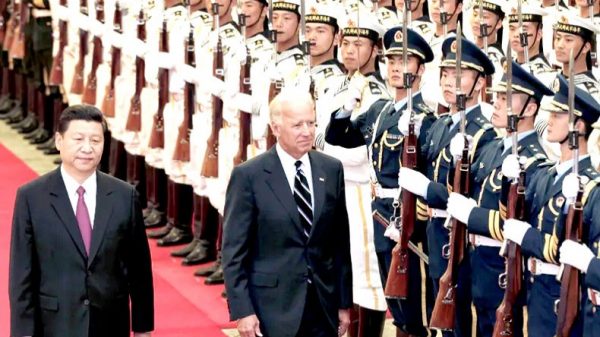

While world leaders debate the Ukraine crisis at the United Nations and news flashes from that battle zone become a part of our daily lives, the most dramatic and dangerous changes may be occurring at the other end of Eurasia, from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific. There, Beijing and Washington are forming rival coalitions as they manoeuvre over a possible war focused on the island of Taiwan and for dominance over a vast region that’s home to more than half of humanity.

And yet, despite the obvious dangers of another war, the crises there are little more than a distraction from a far more serious challenge facing humanity. With so many mesmerised by the conflict in Ukraine and the possibility of another over Taiwan, world leaders largely ignore the rising threat of climate change. It seems to matter little that, in recent months, we’ve been given unnerving previews of what’s to come. ‘Geopolitical divides are undermining… all forms of international cooperation,’ UN secretary-general António Guterres told world leaders at the General Assembly last month. ‘We cannot go on like this. Trust is crumbling, inequalities are exploding, our planet is burning.’

To take in the full import of such an undiplomatic warning from the planet’s senior diplomat, think of geopolitical conflict and climate change as two storm fronts — one a fast-moving thunderstorm, the other a slower tropical depression — whose convergence might well produce a cataclysm of unprecedented destructive power.

Geopolitics of the old cold war

ALTHOUGH the rival power blocs in this new Cold War across Eurasia resemble those of the 1950s, there are subtle differences that make the current balance of power less stable and potentially more prone to armed conflict.

Right after China’s communists captured Beijing in October 1949, their leader Mao Zedong forged a close alliance with the boss of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, that shook the world. With those two communist states dominating much of the vast Eurasian land mass, the Cold War was suddenly transformed from a regional into a global conflict.

In 1950, when that new communist alliance launched a meat-grinder war against the west on the Korean peninsula, Washington scrambled for a strategy to contain the spread of communist influence beyond an ‘Iron Curtain’ stretching 5,000 miles across Eurasia. In January 1951, the National Security Council compiled a top secret report warning that ‘the United States is now in a war of survival,’ which it was in danger of losing. Were actual combat to erupt in Europe, the 10 active US army divisions there could be crushed by the Soviet Union’s 175 divisions. So, the National Security Council recommended that Washington increase its reliance on ‘strategic air power’ to deliver its expanding ‘atomic stockpile.’ In addition, it suggested Washington should match its North Atlantic Treaty Organisation commitment by building a ‘position of strength in the Far East, thus obtaining an active strategic base against Russia in the event of general war with the Soviets.’

With surprising speed, American diplomats implemented that strategy, signing treaties and mutual-defence pacts meant to encircle Eurasia with rings of steel, especially in the form of new air bases. After transforming the just-formed NATO into an expressly military alliance, Washington quickly negotiated five bilateral defence pacts along the edge of Asia with Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Australia. To bolster that continent’s long southern flank, the western alliance then forged two mutual-defence pacts: METO (the Middle East Treaty Organisation) and SEATO (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation). To complete its 360° encirclement of Eurasia, the US formed NORAD (the North American Aerospace Command) with Canada, deploying a massive armada of missiles, bombers, and early-warning radar to check any future Soviet attacks across the Arctic.

Within a decade, the US had constructed an aerial empire, subsuming the sovereignty of the dozens of allied nations and allowing US Air Force jet fighters to fly their skies as if they were their own. This imperium of the clouds would be tethered to the earth by hundreds of US air bases, home to 580 behemoth B-52 bombers, 4,500 jet fighters, and an armada of missiles that, by 1960, allowed the Air Force to claim nearly half the Pentagon’s swelling budget.

Although this defence architecture rested on the threat of thermonuclear war, it introduced a surprising element of geopolitical stability to the superpower confrontation of that era. As a start, it stretched Soviet defences thin along a 12,000-mile frontier and so, strangely enough, reduced the threat that a single, concentrated point of confrontation could escalate into an atomic war. Indeed, during the 45 years of the Cold War, there would be just four moments when nuclear war threatened, all quickly defused: the Taiwan Straits crisis of 1958, the Berlin crisis of 1961, the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, and the Able Archer NATO exercise of 1983. With the Soviets effectively confined, Washington could inflict a maximum cost at a minimum price whenever its rival tried to break out of its geopolitical isolation, first with moderate success in Cuba and Angola and then with devastating effect in Afghanistan, precipitating the collapse of the Soviet Union.

US and China face off

SOME 30 years after that Cold War ended, however, strategic gaps have appeared in Washington’s encirclement of Eurasia, particularly along the continent’s southern flank. Among other things, its strong Cold War era position in the Middle East has weakened considerably. Once subordinated allies have become increasingly independent of Washington’s writ — notably, Turkey (forming an ‘axis of good’ with Russia and Iran), Egypt (purchasing $2 billion in Russian jet fighters), and even Saudi Arabia (doing major oil deals with Moscow). Meanwhile, despite a trillion-dollar, decade-plus US intervention there, Iraq is collapsing into failed-state status, while moving ever closer to Iran.

The most significant gap was, however, opened by Washington’s chaotic withdrawal from its disastrous 20-year war in Afghanistan, which critics quickly branded ‘Biden’s Afghan Blunder.’ Yet that decision was more strategic than it first appeared. China had already been consolidating its dominance in Central Asia through multibillion-dollar development deals with nations around Afghanistan, like Pakistan, and even before that collapse in Kabul, geopolitical strangulation had forced the US military to send any air support for its ground forces there on a 2,000-mile round-trip flight from the Persian Gulf. Now, a full year later, with the US military facing serious challenges in both Ukraine and the Taiwan Strait, that once-controversial withdrawal seems almost strategically prescient.

At the western end of Eurasia, president Biden’s calibrated response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has not only repaired the damage done to NATO by Donald Trump’s attacks on the alliance but fostered a trans-Atlantic solidarity not seen since the coldest days of the Cold War. Apart from the joint effort to arm and train Ukraine’s military, there has been a fundamental, long-term shift in Europe’s energy imports with profound geopolitical implications. After the European Union reacted to Vladimir Putin’s invasion by banning imports of Russian coal and oil, while Moscow cut critical natural gas from its pipelines, the US helped fill the breach by shipping 60 per cent of its swelling natural gas exports to Europe.

To handle those fast-rising imports, the EU is spending countless billions on a crash programme to build costly terminals for Liquefied Natural Gas. To replace the 118 million tonnes of natural gas imported from Russia annually before the war, the EU is scrambling to double its current array of two-dozen LNG terminals, while simultaneously negotiating long-term contracts with producers in America, Australia, and Qatar to construct costly liquification plants (like the $25-billion Driftwood project now underway in Louisiana). With stunning speed, such massive investments at both ends of the energy supply chain are ensuring that Europe’s economic ties to Russia will never again be as significant.

At the eastern end of Eurasia, on the other hand, an ongoing dangerous stand-off with China over Taiwan is complicating Washington’s efforts to rebuild its Cold War strategic bastion in the Pacific. Last October, Chinese president Xi Jinping insisted that the ‘historical task of the complete reunification of the motherland must be fulfilled,’ while, in May, president Biden announced his intention ‘to get involved militarily to defend Taiwan.’ During her controversial August visit to that island, house speaker Nancy Pelosi stated, ‘America’s determination to preserve democracy here in Taiwan… remains ironclad.’ As China’s jets flood that island’s airspace and American warships steam defiantly through the Taiwan Strait, both powers have launched pell-mell naval construction programmes. The US navy is aiming to have at least 321 manned vessels, while China, with the world’s largest shipbuilding capacity, plans a battle force of 425 ships by 2030.

In recent years, China has relentlessly expanded across Asia economically, while building the world’s largest trading bloc, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. In the future, Beijing may even have the means to slowly draw some of America’s allies into its sphere of influence. While Japan still sees the US commitment to Taiwan as part of its own defence and South Korea has shed its usual ambiguity to issue a joint statement about ‘the importance of preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,’ other Asian allies like Australia and the Philippines have taken a more ambiguous position.

Should China launch an invasion of Taiwan — which, warns that island’s foreign minister, might well happen next year — the price of involvement for the US could prove prohibitive. In a series of war game scenarios proposed by a Washington think tank last August, intervention to save Taiwan could cost the US Navy at least 79 per cent of its forces, meaning something like two aircraft carriers, dozens of surface ships, and hundreds of aircraft.

The increasing unreliability of some of Washington’s allies is amply evident along Eurasia’s southern tier. As part of its ongoing strategic realignment, in 2017 Washington ended its 50-year alliance with Pakistan via a Trump tweet condemning Islamabad’s ‘lies and deceit.’ Following Tokyo’s lead, Washington then forged a naval-oriented entente called the ‘Quad’ with three other Asia-Pacific democracies — Australia, India, and Japan.

India is clearly the keystone in this loose alliance by virtue of its strategic position and its growing navy of 150 warships, including nuclear submarines and an aircraft carrier now under construction. Yet New Delhi’s ad hoc alliance with those kindred democracies is proving ambiguous at best. It has indeed hosted most of the Quad’s annual joint naval manoeuvres aimed at checking China in the Indian Ocean. However, it has also joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a key instrument for advancing Beijing’s Eurasian ambitions. Indeed, it was at that organisation’s meeting in Uzbekistan last month that Indian prime minister Narendra Modi publicly rebuked Vladimir Putin over his Ukraine invasion.

Countering the American array of alliances, China is — through its naval expansion and economic development initiatives — challenging Washington’s once-dominant position in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific. Through its trillion-dollar infrastructure investments, Beijing is laying a steel grid of rails, roads, and pipelines across the breadth of Eurasia, matched by a string of 40 commercial ports it’s built or bought that now ring the coasts of Africa and Europe.

Already possessing the world’s largest (if not most powerful) navy, Beijing’s busy dockyards are constantly launching new warships and nuclear submarines. It also recently built its first major aircraft carrier. Moreover, it already has the second largest space network with more than 500 orbital satellites, while achieving a breakthrough in quantum cryptography by sending unhackable ‘entangled photon’ messages more than 1,200 kilometres.

Reflecting its sharpening technological edge, according to the US Defence Intelligence Agency, China has developed sophisticated cyber and anti-satellite tactics to ‘counter a US intervention during a regional military conflict.’ And in July 2021, it conducted the world’s first ‘fractional orbital launch’ of a hypersonic missile that circled the globe at an unstoppable speed of 3,800 miles per hour before striking within 24 miles of its target — ample accuracy for the nuclear payload it could someday carry. In short, the only certainty in any future US-China conflict over Taiwan would be unparalleled destruction as well as an unimaginable disruption of the global economy that would make the fighting in Ukraine seem like a border skirmish.

Environmental cataclysm

AND yet, stunningly enough, that’s not the worst news for Asia or the rest of the planet. The fast-building climate crisis poses a far greater threat. Last February, when the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its latest report, secretary-general António Guterres called it ‘a damning indictment of failed climate leadership.’

In just a decade or two, when global warming reaches 1.5° Celsius, storms and drought will ravage farmlands in even more devastating ways than at present, while reefs that protect coasts will decline by up to 90 per cent, and the population exposed to coastal flooding will increase by at least 20 per cent. The cumulative changes are, in fact, mounting so rapidly, the UN warned, that they could soon overwhelm the capacity of humanity and nature to adapt, potentially yielding a planet that might, sooner or later, prove relatively uninhabitable.

In the six months following the release of that doomsday report, weather disasters erupting in Asia would give frightening weight to those dire words. In Pakistan, annual monsoon rains, turbocharged by warming seas, unleashed unprecedented floods that covered an unparalleled one-third of the country, displacing 33 million people and killing 1,700. Those waters ravaging its agricultural heartland are not even expected to fully recede for another six months.

While Pakistan is drowning, neighbouring Afghanistan is suffering a prolonged drought that has brought six million people to the brink of famine, while scorching the country’s eastern provinces with wildfires. Similarly, in India, temperatures this summer averaged 109° to 115° Fahrenheit in 15 provinces and remained at that intolerable level in some cities for a record 27 days.

This summer, China similarly experienced staggering weather extremes, as the country’s worst recorded drought turned stretches of the great Yangtze River into mudflats, hydropower failures shuttered factories, and temperatures hit record highs. In other parts of the country, however, heavy floods unleashed lethal landslides and rivers ran so high that they changed course. By 2050, the north China plain, now home to 400 million people, is expected to experience killer heat waves and, by century’s end, could suffer weather extremes that would make it uninhabitable.

With world leaders now absorbed in military rivalries at both ends of Eurasia, once-promising international cooperation over climate change has virtually ceased. Only recently, in fact, China ‘suspended’ all climate talks with the US even though, as of 2020, those two powers were responsible for 44 per cent of the world’s total carbon emissions.

Last November, just four months before the Ukraine war started, the two countries issued an historic declaration at the UN’s Glasgow Climate Change Conference recognising the ‘urgency of the climate crisis’ and stating that they were ‘committed to tackling it through their respective accelerated actions in the critical decade of the 2020s…to avoid catastrophic impacts.’ To honour that commitment, China agreed to ‘phase down’ (but not ‘phase out’) its reliance on coal starting in 2025, just as the US promised ‘to reach 100 per cent carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035’ — neither exactly a dream response to the crisis. Now, with no climate communication at all, things look grim indeed.

Not surprisingly, the collision of those geopolitical and environmental tempests represents a mindboggling threat to the planet’s future, giving the very idea of a cold war turning into a hot war new meaning. Even if Beijing and Washington were to somehow avert armed conflict over Taiwan, the chill in their diplomatic relations is crippling the world’s already weak capacity to meet the challenge of climate change. Instead of the ‘win-win’ that was the basis for effective US-China relations for nearly 30 years, the world is faced with circumstances that can only be called ‘lose-lose’ — or worse.

TomDispatch.com, October 16. Alfred W McCoy is the Harrington professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of US Global Power. His new book, just published, is To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change.