People’s uprising and betrayal of the democratic cause

- Update Time : Tuesday, December 6, 2022

- 70 Time View

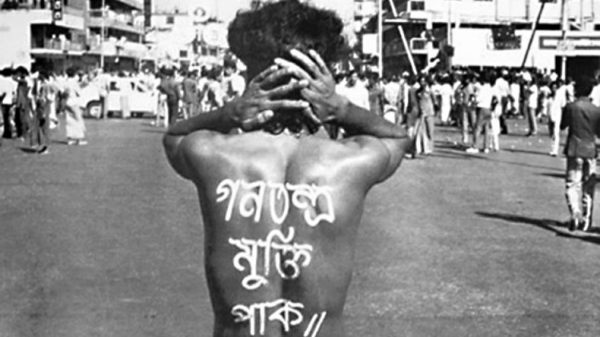

Bangladesh entered a new era of its political history with the fall of General HM Ershad’s military junta 32 years ago on this day — December 6, 1990. General Ershad illegally took power on March 24,1982. The first resistance against the regime came from the country’s student community while it took an organised shape after the student bodies created the Students’ Action Committee in February 1983 to fight against the military regime and restore democratic process in the country. The students and the illegally installed military regime stood face to face in mid-December and the latter fired shots on the huge procession of the protesting students, killing a couple of them and injuring hundreds. The state oppression only refuelled the democracy movement and the Students’ Action Committee this time formulated a 10-point charter of demands, obviously including an end to military rule. The 10-point charter also included the formulation and implementation of a pro-people secular democratic education policy, introduction of a truly representative governing system, meeting the legitimate demands of the people belonging to the working classes, particularly the industrial workers and the peasants, etc. The Students’ Action Committee successfully spread its 10-point movement across the country.

Meanwhile, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund strongly recommended ‘structural reforms’ of the country’s economy, under which the military regime undertook a massive programme of privatisation of the state-owned industries and public enterprises. Thus, the state-owned industries and enterprises were handed over to individuals and groups at throwaway prices, creating a lumpen class of the rich.

The so-called reforms programme duly enraged the public sector industrial workers and subsequently the labour bodies got united and created the Sramik Karmachari Oikya Parishad, a joint platform of the labour forces, put up effective resistance against the military regime implementing WB and IMF policies. However, as the Sramik Karmachari Oikya Parishad took to the street, the Students’ Action Committee supported the labour movement while the military regime made all-out efforts to brutally supress the democracy movement.

Earlier, following the rejuvenated student movement after the government crackdown on the protesting students, the main stream political parties started organising themselves and eventually there emerged two political alliances — one led by the Awami League which was consisted of 15 political parties and groups including the left-wing organisations and the other led by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party comprised seven parties and groups. They, in the course of the movement, formulated a five-point charter of demands focused primarily on the demand for the resignation of General Ershad and the holding of free and fair national elections. Both the alliances made public pledges that they would not take part in any elections held under the military regime of General Ershad and that, if and when voted to power, they would meet the ‘legitimate demands’ of the Students’ Action Committee and the Sramik Karmachari Oikya Parishad.

Thus, the country witnessed a massive political movement, first ever in the independent Bangladesh, in which the forces of students and workers, professional bodies and the people in general rallied round the demand for democracy. The peasants’ organisation also joined the movement, which was progressing through the supreme sacrifices of many a protester. The Ershad regime almost came to the verge of collapse in 1986. But, alas, in violation of the repeated public commitment, the Awami League suddenly resolved through backdoor negotiations with incumbents of the day, without even consulting most partners in its 15-party alliance, let alone the leaders of the other alliances, to participate in the elections held under Ershad regime. Subsequently, some left-wing parties left the League-led political combine to form their own, five-party alliance, which continued the anti-Ershad movement along with other forces — the students, the workers and the seven-party alliance. The League’s departure from the people’s struggle for democracy to be the main opposition in Ershad’s Jatiya Party dominated parliament weakened the movement, giving the illegal regime a lease of life for four more years.

Nevertheless, disillusioned about the Ershad regime, the League quit the parliament and came back to the protesting people. Finally, after a couple of years of political movement since then, the Students’ Action Committee was broadened to incorporate the BNP’s student wing, a large popular student body those days, while the new platform came to be known as All-Party Student Alliance that re-wrote the original 10-point charter, making it to be a full-fledged comprehensive programme for democratising the state, economy, education, and, of course, the system of governance. Besides, the 10-point charter clearly demanded the separation of the judiciary from the executive branch of the state, the prohibition of the use of religion in politics, the confiscation of illegally acquired wealth in favour of the state, a credible investigation into the murders of protesters during the movement and ensuring punishments for those found guilty and so on and so forth.

It was after this forging of this broader unity among the student bodies, and that too based on the revised 10-point-programme, that the decade long anti-Ershad movement reached its peak in the first week of December 1990. The regime collapsed on December 6, when Ershad was forced to quit power. Since then, with a small interval of a military-driven government between 2007 and 2008, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and the Awami League ruled the country, but the blood-soaked 10-point charter of demands remains almost entirely unmet. Instead, history has witnessed both the mainstream parties eager to get the once deposed General Ershad and his Jatiya Party as an ally, at different points in time, for the sake of enjoying state power. What a horrible betrayal. Meanwhile, the bodies of the martyrs must have turned in the grave at every initiative of the AL and the BNP to befriend the Jatiya Party for sheer power.

However, one can easily say that once a set of genuine demands comes up in a society, and that too through the process of people’s movement, it never dies down. It just remains dormant and surfaces again and again until it is fully realised. The democratic spirit of the All-Party Student Alliance’s 10-point charter of demands also remains dormant in Bangladeshi society and new forces of democracy will come forward someday to realise those demands.

Dr Akhtar Sobhan Khan Masroor, presently a writer and researcher, was a leader of the Students’ Action Committee in the mid-1980s and a central leader of the All-Party Student Alliance in 1990.