Sketch of a jab and resistance

- Update Time : Saturday, July 8, 2023

- 57 Time View

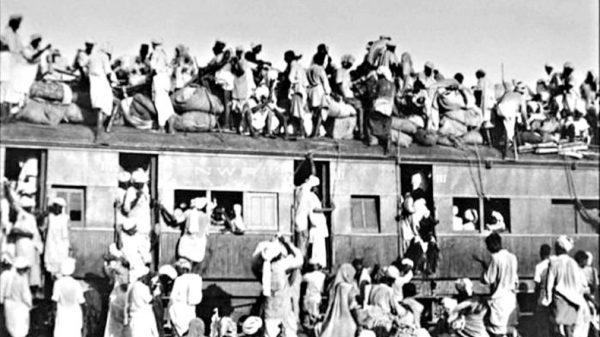

THE mainstream abstains from discussing two aspects of the partition, a dagger-act: the harm to people’s struggle for a democratic, dignified life free from injustice and exploitation, and resistance by and suffering of the Communist Party, the political party standing for the exploited, to the dagger-job. Years back, it was told in detail in Frontier, the famous independent socialist weekly from Kolkata.

It is known that subverting people’s struggle is a fundamental loss to people striving for building up an advanced democratic society.

Considering the hardship borne and sacrifice made by people to build up their organisations and struggles help perceive the extent of loss they face with the negative effect on these. Moreover, overwhelming an environment of struggle with an atmosphere of hatred along a sectarian line is a bigger loss, as the atmosphere of hatred makes organising struggles more difficult. The pre- and post-partition East Bengal, now Bangladesh, is a burning example of the injury to people’s struggle and the Communist Party’s resistance and suffering. Igniting the communal fire in the period was a blitzkrieg by the exploiters. The people and the political party upholding their interests — the Communist Party — were not politically and organisationally equipped to counter the full throttled campaign by the dominating interests. The jab was made in 1946, and the job continued in post-’47 East Bengal. The dagger-job carried all marks of reaction — an onslaught by reaction with the face of sectarianism.

Instead of going into detail, following is a very brief description of the impact of the exploiting classes’ political move on the people, on the people’s struggle in Bengal. Veteran Communist leaders/organisers/activists from East Bengal, now Bangladesh, write in their autobiographies/memoirs/history books:

Fears: Fears gripped the situation. There were assaults and murders in many parts of the province (then Bengal). Properties were taken away. A collective consciousness of vulnerable minority status occupied a part of the population.

Political activities: Political activities were affected. It diminished. Organisational strength was weakened; number of members/activists decreased; and income of the party, contributions from the common people, diminished drastically. Mass organisations and trade unions went to oblivion or lost activity. Mass movements and class movements were harmed or thwarted. Many union activists were terminated from their jobs. Many activists were put behind bars. Many leaders and activists lost homes. Many union activists who were employed were tortured. Even, torture and killing were carried out within prisons. Many activists with progressive politics left the eastern part. Persistent and widespread anti-Communist Party propaganda and lies were carried out by the political parties and a section of media representing the exploiting interests, and the state machine. Liaquat Ali Khan, the then prime minister of Pakistan, also took part in this propaganda campaign. Assault by class enemies including the state machine were carried out. Communist Party’s isolation from people began. Labour, whatever was there in the part, was terrorised. An overwhelming atmosphere of sectarian/communal hatred was created; and it turned difficult to organise the public in the face of terror and adverse propaganda. The ruling politics organised a section of the workers with retrogressive ideas along sectarian line against rest of the workers trying to organise labour’s struggle. The part under the sway of retrogressive ideas broke meetings of and assaulted the progressive part of the labour. The Communist Party with its already dwindled strength was failing to organise public against sectarian riots despite repeated efforts in the urban and rural areas under its influence. The Communist Party was the target; and the party felt a negative impact.

The full descriptions reveal the anti-people, anti-working class, and reactionary character of the sectarian politics that is associated with the partition/bifurcation.

The working classes, their politics and organisations, their solidarity and fraternity in other parts of the subcontinent had more or less similar experiences.

It was a class war against the exploited, the working classes. It was a class war by the exploiters, with imperialism at the helm.

Resistance: However, there were incidents of resistance, and those are examples of possibilities the working people could have done. Nitish Sengupta writes: ‘Even when communal violence was rampant in Calcutta and Noakhali, the Muslim and Hindu peasants of the Tebhaga movement [a movement by the share croppers] in predominantly Muslim Rangpur and Dinajpur were fighting […] and opposing Partition.’

Also in other areas in the eastern part of Bengal, Communist activists carried on publicity work in villages for months. They organised meetings in villages, and made people aware of the curse of communalism. The efforts kept the area free from communal riot.

The Communist Party organised committees to maintain peace in some areas, defying Section 144, Hindu and Muslim workers brought out peace processions in a town. They defied Section 144 to march in the processions, which decreased mutual mistrust between the two communities in the town to some extent. The student activists of the Communist Party in Dhaka University organised a peace procession, which was joined by thousands of citizens, about 15,000, like a deluge, irrespective of religious identity, but the police obstructed the procession at a stage. However, they marched ahead, and within a day the situation in the town returned to normal.

Armed struggle: There are instances of organising people’s struggles including armed struggle in a number of parts of the eastern part of Bengal, which were joined by hundreds of thousands of peasants. But it was not possible to extend support to these movements from urban areas due to the prevailing atmosphere of communal violence. However, these movements saved a number of rural areas from fratricidal riot to a great extent. Many branches of the Communist Party in the northern and eastern parts of East Bengal got strengthened as a result of these movements. In areas, the Party could encourage a significant part of a community to refrain from migrating to the western part of Bengal. But, at last, the dominating classes’ and a section of government machine’s ultra-communal activities prevailed, and an environment of fear spread among the Hindus. In Dhaka, many militant processions by labourers and students were organised. In areas in the eastern part, the common people opposed efforts to organise riots by the reactionary forces. As a result, riots could not be organised. In one area, the Communist Party’s volunteer force resisted rioters.

Thus, in brief, the working people’s struggle subverted by a jab of the exploiting interests while the working people tried to resist the dagger-job.

A comparison

A COMPARISON can be made. Almost at the same time, peoples in two lands in the same continent — Asia — were waging their wars for liberation. One was in Vietnam, and the other was in China. Peoples in both of these lands were pushing away or throwing out imperialism. Vietnam threw away two imperialist powers, and the imperialist powers could not play the trick of any sectarian divide that could push one part of people against another. China had the same trajectory — no division among the people in opposing imperialism, in attaining liberation.

Obviously, this subcontinent and those two lands were not the same in many terms that include historical development, state of economy and politics of that time, political power structure, people’s organisations, mobilisation and force, classes — class composition, class alignment, development of classes, class power, etc.

Despite these differences, neither in Vietnam nor in China, no communal or fratricidal feud created obstacles to the people’s journey forward. Moreover, in Vietnam, the people continued with their fight to reunify their country that was politically, not along sectarian line, divided into two parts by the imperialists. In China, imperialism could do no such or any other type of division.

Can this comparison be put as a question? Can this comparison, if it comes up as a question, help find out an answer to the failure in aborting exploiting interests’ trick of sectarian divide that pushes people into warring camps and chokes people’s journey towards a life without masters of exploitation?

Why the working people?

It may be questioned: Why this article focuses on the working people’s struggles?

The single question carries many answers:

— The working people, the exploited, are the biggest part of humanity, the biggest part of the population in this subcontinent.

— The working people in this subcontinent, like in all lands, is the most exploited, tortured, tormented part of the population, although they with their labour power create resources, elements of luxury and comfort for all others.

— As class power, the working people carry the prospect of making advances in society, as they have no stake in interest connected to backwardness.

— Today, many discussions on many subjects ranging from land and rights to ecology and climate crisis go on, but the question of contradiction between labour and capital, and the question of the working people from a class point of view remain out of agenda, or go least discussed, although this is one of the burning issues; and discussions will remain superficial if the issues are not examined in the perspective of the contradictions.

Based on these arguments, today, the issue discussed in this article has focused on the working people.

While people are divided along sectarian line, people are robbed of awareness and organisation, robbed of a sense of solidarity and fraternity. Awareness and organisation of people are people’s resources that they build up slowly, with much struggle and sacrifice. Organisations are much needed resources of people.

These resources were robbed by the masters in command of the situation as part of the class war it was conducting in this subcontinent, and the people’s political destiny was appropriated by a reactionary clique with its political power and the coercive power of state; and the people faced persecution, torture and deprivation. The exploiting classes, like a band of robbers, joined together to rob the people and snatched away people’s struggle for a dignified, democratic and prosperous life.

Concluded.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka. The series is a modified version of a lecture delivered on an occasion organised by the Vivekananda chair, Mahatma Gandhi University, India, on April 27, 2023, and based on an essay, ‘Class War in East Bengal, 1946 and Communist Party’, published in the Autumn Number, 2015 of Frontier, Kolkata.