The rise of counter middle class?

- Update Time : Thursday, January 25, 2024

- 46 Time View

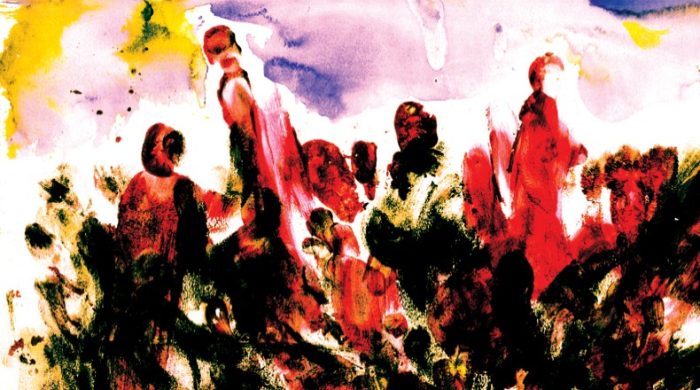

ONCE most, if not all, thought of the middle class as a single monolithic social economic construct. This was particularly so during the period from 1947 to 1971. It was the great Ekushey era when poets, writers and painters were considered the main spirit behind the social and political progress of society.

Sushil: February elite transition

THE February firing of 1952 affirmed this status and the killings of 1971 confirmed this further. However, it was not the only reality but the sushil middle — urban dominantly with village roots, particularly in observing social festivals — were on the dominance and the rest were ignored.

This middle, therefore, had a single face which was based on their role in politics as well as their chosen craft, be it education or media. They were considered architects of the resistance to the Pakistan state domination and the struggle was symbolised by culture and language.

While it is a fact that some were also accused of being pro-Pakistani and opportunist as well, that is always the case. The role of the intellectuals imagined as pure knights in a white shining armour is only matched by the amount of mud that is freely distributed amongst the same crowd.

But overall, there was no contest. However, within the bowels of history, changes were in the making as the phase passed from the state formation to the state construction stage. The economy began to change, new inputs and challenges arrived and class formations and contests began to take new shapes.

The old middle class, the traditional liberal Left types were there, but the Right, according to their viewpoint, began to rise, too. The liberal Left tried to shut them down by developing a constitution based on their gospel but in an informal state, it did not have the reach and the values upheld in that document had limited appeal, also.

The traditional liberal Left never thought that there could be a contest of their position, but times had changed. The traditional dependence of the old middle was on the state machinery and the patrons produced by connection capitalism. While in the earlier, 1947–71, phase, they thrived on contesting the state, they could ensure survival only by declaring consensus with the same after 1971.

Thus, they were increasingly of the old fashioned collaborator variety with some true believers in the state thrown in. This significantly reduced their clout. However, their dependence on the state patronage that is the formal sector economy was their primary hindrance and signature.

Emergence of new middle

BY 1978, the peasant economy had recovered sufficiently from the impact of the 1971 war to fund a key poverty alleviation tool — migration. This was, of course, related to the middle poor who had some land that could be sold to fund migration; and, the transition began. By 1990, they had gathered sufficient strength and it was impossible to ignore the rise of the new economy centred around migration and soon the ‘new’ culture began to rise as well. And, thus, was born the new middle that was dependent on the informal sector economy. This was led culturally by the religious clergy of the rural professional variety.

The primarily rural area-driven middle class was the traditional middle that had lost out to the traditional middle. And their area of focus was the culture of the rural areas that is driven by religious impulses of the social variety.

The old middle is liberal Left and is a by-product of the formal state, a product of colonial continuity. For the sake of the tagging of convenience, we may call the traditional sushils roughly as Tagorean Marxists. Their sensibilities were born under the colonial era; hence, their ideas are also located in western paradigms whose roots of introduction lay under colonialism. It was the standard state funded middle class.

Migrants funded rural middle

THE new middle — produced by informal economics — is actually older and their roots lie in the pre-colonial society. They are located in the rural areas, mostly funded by remittances and not by the state. Their economic health is independent of the functioning of the formal ruling class. To that extent, they represent social impulses as opposed to the state impulses of the urban sushil class.

What this means is the rise of competition between two elites, one located in the social, rural and informal economy and the other in the urban, state based formal economy. One is based on collaboration and the other is based on competition. One is west-driven while the other is not and is probably more organic. One is not as important to the state as it is willing to listen to what is told and has little independence on its own.

The other is more independent but again very dependent on the funding social segment and rural scenario where iot can spin its theology into popular social products.

But the monopoly has been broken of the traditional middle-based middle class and it is the other class that is displaying more clout. As we delve more into a comparative analysis, we can gauge its strength from its activities and conflicts. This relates to the competition, collaboration and conflict that are part of the transition phase as both the state and society is made and unmade.

It also may reflect the reality of internal class conflicts as two middle joust for socio-political dominance.

Afsan Chowdhury is a researcher and journalist.