Old mole comes back

- Update Time : Saturday, June 29, 2024

- 43 Time View

Loyal communists and virulent anti-communists were often cut from the same cloth. They occasionally talked much the same talk, only from opposite sides of the barricades. The more the ex-reds named names and tried to lose their pasts the more enemies they made and the more their reputations were tarnished, though sometimes, careers briefly flourished, writes Jonah Raskin

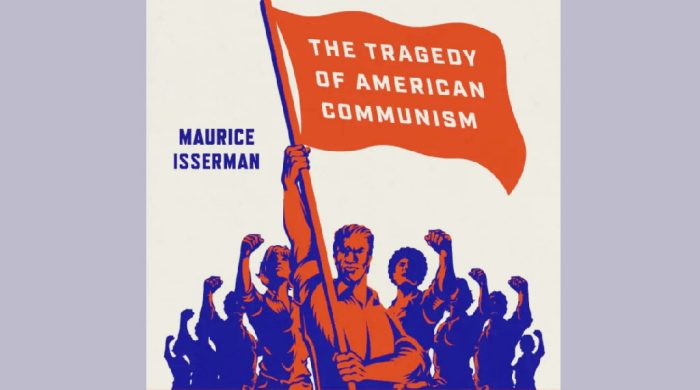

REDS — the title of Warren Beatty’s Bohemian/Bolshevik love story that features John Reed and Louise Bryant — is also the title of Maurice Isserman’s new book subtitled, The Tragedy of American Communism. Issermam is the author of three other books about communism with a big letter C and a small letter c: If I had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left; California Red: A Life in the American Communist Party; and Which Side Were You On? The American Communist Party During the Second World War.

Isserman’s Reds is dominated by biographies of US CP bureaucrats including William Z Foster and Earl Browder, who coined the slogan ‘Communism is 20th century Americanism’, plus Gus Hall and a few women such as Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the original ‘rebel girl’, and Dorothy Healey, who anchored the LA CP before and during its underground days in the 1950s.

Isserman doesn’t spend much time with rank-and-file members, nor does he show what daily life was like for CP members in, say, Pittsburgh in 1928, San Francisco in 1934 and Washington DC in the 1940s when Marxists, genuine leftists, and loyal American citizens worked for FDR’s New Deal.

US CP leaders bowed down to Soviet commissars, but day-in and day-out the comrades weren’t thinking of Moscow and Stalin, but rather about hawking copies of The Daily Worker, preventing an eviction by a landlord, and persuading assembly line workers to join the Congress of Industrial Organisations, the radical alternative to the American Federation of Labour.

Isserman aims to tell a tale of tragic proportions, but his book might also be appreciated as a comedy of errors worthy of a Groucho Marxist like Abbie Hoffman. I remember that when the State of New York revoked the driver’s license for CP chief, Gus Hall, he traveled to and from his Manhattan office in a chauffeur-driven car. Only in America and perhaps in the Soviet Union could communists ride like plutocrats.

In his prologue, Isserman writes that ‘In the 1930s in the period of its greatest influence, the Communist Party fought for causes like unemployment insurance, social security and racial equality that in years to come helped make the United States a better, fairer society.’ But instead of exploring the best, Isserman emphasizes the worst, especially the adherence to Moscow which isolated comrades from the blue collar workers they were supposed to bring into the party.

My brother ‘D’ plowed through Reds before I did. ‘It’s like reading family history’, he said. Now that I’ve read the book I know what he meant. Many of the events and the political figures that Isserman writes about flickered in and out of my consciousness when I was a boy who grew up with a mother and father who belonged to the CP. They never really shed their allegiance to communism. As a kid, I heard about the Bolsheviks, the battle of Stalingrad, John Reed and his Ten Days that Shook the World, the briefly earthshaking ‘Duclos Letter’, and Khrushchev’s secret speech about the crimes of Stalin and the cult of the personality. Once it went public it shook up the communist world.

Isserman acknowledges the off-spring of CP members, and not just Bettina Aptheker, daughter of Herbert, author of American Negro Slave Revolts. We numbered in the tens of thousands; a history of American reds might be assembled from our points of view, not as ‘red diaper babies’, a demeaning term, but rather as young people who could and did make up our own minds about the Bomb, the Cold War and the Iron Curtain.

I never joined the CP and never wanted to, but during my early years I learned about capitalism, communism, the proletariat and the bourgeois which proved useful from time to time, though those terms could also become largely rhetorical and narrowly academic. I remember a conversation with Tillie Olsen, the author of Yonnondio from the Thirties and her famous short stories, ‘Tell me a Riddle’ and ‘I Stand Here Ironing.’ Tillie objected to the title for a book — The Proletarian Literature of the United States — to which she contributed an eye-witness account of the 1934 SF General Strike. ‘What’s wrong with the phrase working class?’ she asked me. ‘It’s better than proletarian.’ ‘Solidarity forever’, Tillie would say after every visit I made to her Berkeley apartment.

Read Reds and you understand why communism appealed to patriotic citizens in the 20th century in the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world: the economic crisis of the 1930s; the rise of fascism; imperialist wars and the racism and injustice that confronted defendants such as the Italian immigrants, Sacco and Vanzetti, along with the young Black men known as ‘the Scottsboro Boys’, and Eugene Victor Debs, who ran for president five times and went to jail for violating the infamous Sedition Act that jailed Americans for uttering innocent remarks.

What Isserman doesn’t explain, as least not to my satisfaction, though he has studied the subject for decades, is why — after the fall of the Soviet Union, revelations about the Gulags and news of the bloodshed at Tiananmen Square — communism has continued to tug at the hearts and minds of citizens in the US, Russia, India and elsewhere. A few weeks ago in a book store in San Francisco, I heard Malcolm Harris, the author of Palo Alto, call himself ‘a communist.’ Other intellectuals and authors in his generation belong to the growing chorus of self-proclaimed reds.

Shortly before she died in 1996, the muckraking journalist, Jessica Mitford, told me she lamented the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of communism as she had known it for most of her life. Old attachments don’t die easily; loyalties often count more than ideologies. And hopes for a new world without the rapacity of class society, appeal eternally.

In the coda to Reds, Isserman writes, ‘The Communist Party USA still exists’, though that existence isn’t on his agenda. Still, it seems worthwhile to ask, ‘Why does the God that supposedly failed continue to resurrect itself with help from friends and comrades?’ Perhaps the current rebirth is a sign that the contradictions of capitalism haven’t dissipated and because ‘the masses’ hunger for an organization that will give them tools to fight for freedom from fear, poverty, an arrest, incarceration and deportation.

Communism is back. It won’t go away even if and when Trump is elected president and the Trumpers target liberals, leftists, radicals, feminists, union leaders, black ministers and their congregations. For decades, CP members cried ‘fascism.’ I grew up with that word ringing in my ears. Now, perhaps, what comrades have seemed to fear most and yet what some of them have wanted, will come true. Under fascism, communism can seem like the only viable alternative.

By the end of Reds I wondered if the ‘tragedy’ isn’t also about the anti-communist crusade and the US, too, the nation which saw ‘reds’ even when reds were largely absent from picket lines and sit-in strikes.

In the early 1960s, when I was a college student, I heard ex-communists say that there were more FBI agents in the CP than genuine reds. Perhaps so.

Loyal communists and virulent anti-communists were often cut from the same cloth. They occasionally talked much the same talk, only from opposite sides of the barricades. The more the ex-reds named names and tried to lose their pasts the more enemies they made, and the more their reputations were tarnished, though sometimes, as in the case of director, Elia Kazan, careers briefly flourished.

In his last sentence, Isserman writes that the ‘church and the citadel’ of the CP, ‘stood for and guarded nothing but ashes.’ Perhaps he’s forgotten that the phoenix bird rises from its own ashes and that as Marx observed, ‘We recognize our old friend, our old mole, who knows so well how to work underground, suddenly to appear: the revolution.’

CounterPunch.org, June 28. Jonah Raskin is the author of Beat Blues, San Francisco, 1955.