The Indian queens who modelled for the world’s first vaccine

- Update Time : Monday, September 21, 2020

- 263 Time View

When Devajammani arrived at the royal court of Mysore in 1805, it was to marry Krishnaraja Wadiyar III. They were both 12 years of age and he was the newly minted ruler of the southern Indian kingdom.

But Devajammani soon found herself recruited for a more momentous cause – to publicise and promote the smallpox vaccine. And her unwitting role was captured in a painting commissioned by the East India Company to “encourage participation in the vaccination programme”, according to Dr Nigel Chancellor, a historian at Cambridge University.

The cure for smallpox was fairly new – it had been discovered just six years before by Edward Jenner, an English doctor – and met with suspicion and resistance in India. Not least because it was being championed by the British, whose power was rising at the turn of the 19th Century.

But the British would not give up on their grand scheme to inoculate Indians – they justified the cost and effort of saving “numerous lives, which have yearly fallen a sacrifice” to the virus with the promise of “increased resources derived from abundant population”.

What followed was a deft mix of politics, power and persuasion by the East India Company to introduce the world’s first ever vaccine to India, their biggest colonial enterprise. It involved British surgeons, Indian vaccinators, scheming company bosses and friendly royals – none more so than the Wadiyars, indebted to the British who had put them back on the throne after more than 30 years of exile.

The women in the painting

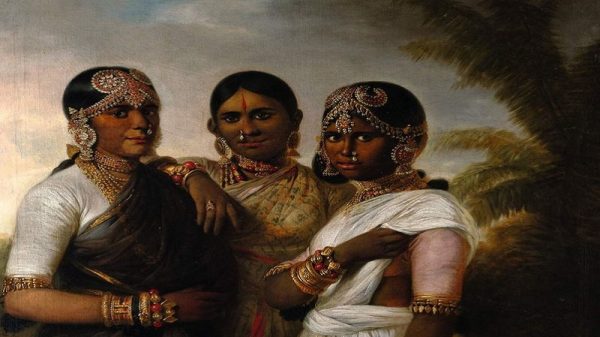

Dr Chancellor believes this painting, dated to around 1805, is not just a record of the queen’s vaccination but also a window into how the British effort unfolded.

The portrait, an arresting rendition in oil on canvas, now sits in the Sotheby’s collection, priced between £400,000 to £600,000. Its subjects were unknown – and thought to be dancing girls or courtesans – until Dr Chancellor stumbled upon it.

He says he “immediately felt this was wrong”.

He identified the woman on the right in the painting as Devajammani, the younger queen. He said her sari would have typically covered her left arm, but it was left exposed so she could point to where she had been vaccinated “with a minimum loss of dignity”.

The woman on the left, he believes, is the king’s first wife, also named Devajammani. The marked discoloration under her nose and around her mouth is consistent with controlled exposure to the smallpox virus, Dr Chancellor said. Pustules from patients who had recovered would be extracted, ground to dust and blown up the nose of those who had not had the disease. It was a form of inoculation known as variolation, that was meant to induce a milder infection.

Dr Chancellor cited details to support his theory, which was first published in an article in 2001. For one, the date of the painting matches the Wadiyar king’s wedding dates and the court records from July 1806, announcing that Devjammmani’s vaccination had a “salutary influence” on people who came forward to be inoculated. Two, as an expert in Mysore history, Dr Chancellor is certain the “heavy gold sleeve bangles” and “the magnificent headdresses” are characteristic of Wadiyar queens. Also, the artist, Thomas Hickey, had earlier painted the Wadiyars and other members of the court.

And most important, he wrote, is the “compelling candour” with which they engage the viewer. Half-smiling royal women striking a casual pose for a European painter is rare enough to raise eyebrows. And the Wadiyars would have not have risked a scandal, Dr Chancellor said, for a run-of-the-mill portrait.

But what if it was quid pro quo?

It was a heady time for the East India Company. In 1799, it had defeated one of its last great foes, Mysore’s ruler, Tipu Sultan, and put the Wadiyars in his place. But British dominance was still not assured.

So, according to Dr Chancellor, William Bentick, the governor of Madras (now Chennai), sensed a political opportunity in battling a deadly disease.

And the British were keen on getting the vaccine to India to “protect the expat population,” says Professor Michael Bennett, a historian who has documented the arduous journey of the vaccine to India in his book, War Against Smallpox.

In India, smallpox infections were high and fatalities common – symptoms included fever, pain and severe discomfort as pustules broke out across the face and body. Those who survived were often scarred for life. For centuries, it had been treated with variolation, accompanied by religious rituals. Hindus saw it as a sign of the wrath of Mariamma or Sitala, the goddess of the pox, and sought to propitiate her.

So the advent of a vaccine, which consisted of cowpox virus, was not welcome. And Brahmin variolators, or “tikadars”, resented the new procedure that threatened their livelihood.

“The major concern was the pollution of pushing into their healthy child a cattle disease,” Prof Bennett said.

“How do you translate cowpox? They brought in Sanskrit scholars and found themselves using terms locals would have used for far worse diseases. And there was alarm that cowpox might devastate their cattle.”

There was another, bigger problem – the most effective way to vaccinate was to do it “arm-to-arm”. Using this method, the first person would be vaccinated by smearing the vaccine onto their arm with a needle or a lancet. A week later, when a cowpox pustule developed in that spot, a doctor would cut into it and transfer the pus on to the arm of another person.

Sometimes, the lymph from the arm of a patient would be dried and sealed between glass plates to be transported elsewhere, but it usually did not survive the journey.

Either way, the vaccine was passing through bodies of all races, religions, castes and genders, and that ran counter to unyielding Hindu notions of purity. How better to overcome these fears than enlist the help of Hindu royals, whose power was tied to their bloodlines?

The journey of the vaccine to the Wadiyar queen probably began – in India at least – with the three-year-old daughter of a British servant named Anna Dusthall.

Starting in the spring of 1800, the cowpox vaccine was sent by ship from Britain in the form of dried lymph samples or via “vaccine couriers” – a human chain of people being inoculated arm-to-arm to keep the vaccine going during the voyage. But none of those vaccinations took once they arrived in India.

After several failed attempts, dried vaccine matter was sealed between glass plates and successfully delivered from Vienna to Baghdad in March 1802. It was then used to vaccinate an Armenian child and the lymph from his arm was taken to Basra, in Iraq, where an East India Company surgeon established a supply arm-to-arm that was sent to Bombay (now Mumbai).

On 14 June, 1802, Anna Dusthall became the first person in India to be successfully vaccinated against smallpox. Little else is known about her, except that she was “remarkably good tempered”, according to the notes of the doctor who vaccinated her. Dusthall was partly of European descent, Prof Bennett said, but her mother’s heritage is unknown.

“We know all vaccination in the subcontinent came from this girl,” he said.

The following week, five other children in Bombay were vaccinated with pus from Dusthall’s arm. From there, the vaccine travelled, most often arm-to-arm, across India to various British bases – Hyderabad, Cochin, Tellicherry, Chingleput, Madras and eventually, to the royal court of Mysore.

The British did not always record the names of people who kept the supply going, but they did note that it passed through many “unexceptional bodies” – there are mentions of three half-caste children who re-established supply in Madras, and a Malay boy who ferried the vaccine to Calcutta (Kolkata).

It’s not known if the young queen Devajammani was vaccinated with dried lymph or from the pus of an earlier patient. There is no mention of anyone else in the family or at the court being vaccinated, Dr Chancellor said.

That would not have been unusual because there are reports of other royals being vaccinated.

But none memorialised it in a portrait. The credit for that politicking, according to Dr Chancellor, goes to the king’s grandmother, Lakshmi Ammani, who had lost her husband to smallpox. He believes she is the woman in the middle of the portrait of the three women, buttressing the Wadiyar stamp of approval for the vaccine. The “oval face and enormous eyes” are typical of the family, he adds.

Dr Chancellor says the painting was possible because she was in charge – the king was too young to object and the queens were too young to refuse.

The campaign continued as people came to realise the benefits of the procedure, and many tikadars switched over from variolation to vaccination. By 1807, Prof Bennett estimated, more than a million vaccine doses had been administered.

Eventually, the painting made its way back to England and disappeared from public view.

It did not resurface until 1991, when Dr Chancellor spotted it at an exhibition and rescued the women from obscurity, giving them a place in one of the world’s first immunisation campaigns.