Western China and the New Silk Road

- Update Time : Saturday, October 26, 2019

- 244 Time View

COMING to China every few months has almost become a regular occurrence for me, though this time I am in a part of China I have not been to before.

China’s developmental model has for decades been tilted towards export-based manufacturing. This model has brought immense benefits to China. Its eastern coastal regions, Guangdong and its hinterlands in particular, have flourished, while China inland and to the west has lagged behind this hectic developmental pace.

I spent a day in Beijing en route, and was struck by how much cleaner the air was. When last there eight years ago the air I breathed seemed to have more sulphur than oxygen in it — this time my mask with a respiratory filter was not needed.

It was probably only a matter of time before Beijing’s air quality improved. The ruling elite are based here because it is the capital, and they were not going to want to keep a breathing apparatus next to them at all hours. Significant measures were bound to be taken, and they have been.

Delhi, where I’ll be early in the new year is another matter — I’ll definitely need my respiratory mask there.

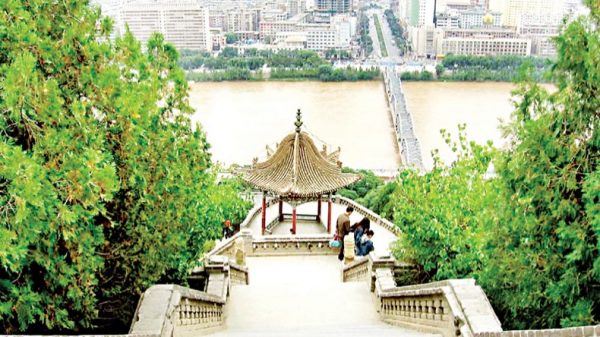

I spent several days in Lanzhou, a city of five million people in western China’s Gansu province. Lanzhou shares an arid plateau with nearby Mongolia, and is 1525m/5003ft above sea level.

Lanzhou is a reflection of the government’s attempt to deal with the relative lack of development outside China’s eastern coastal areas.

Once ranked as one of China’s top-10 polluted cities, Lanzhou has been cleaned up by reducing smoke-stack pollution and ridding the Yellow River of pollutants (though several smoke-stacks were still belching smoke as I was taken around the city).

The river, although 3400km/2113m from its mouth in the China Sea, is wide and swift-moving. Factories are no longer allowed to dump pollutants in the river locals call Mother River, which was once likened to an open sewer.

Where there’s a political will, it’s really not impossible to get such things done.

Apart from pollution, desertification due to its proximity to the Gobi Desert has been a major problem for Lanzhou. A massive tree-planting scheme has been successful in halting the onward-march of the desert.

Once a stopping-off point on the ancient Silk Road, Lanzhou is close to some major historical sites. Tourism is already a big earner for the local economy, and infrastructure is being enhanced to make life more convenient and attractive for the growing number of tourists. Six-lane roads are being constructed all over the city, and Lanzhou’s two existing metro lines are being augmented by more lines that will cover the entire city when completed.

This focus on infrastructure is a key component of China’s Road and Belt initiative, whose official goals are ‘to construct a unified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, ending up in an innovative pattern with capital inflows, talent pool and technology database’.

In addition to infrastructure investment, the Road and Belt initiative will also emphasise education, construction projects, railway and highway expansion, enhancement of power grids and iron and steel production.

The Initiative will cover more than 68 countries, encompassing 65 per cent of the world’s population and 40 per cent of global GDP (using 2017 figures).

This economically-driven cosmopolitanism matches that of the Old Silk Road, whose known travellers included (in addition to the Chinese) Koreans, Levantines, Armenians, Persians, Turks, Russians, Venetians (Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo, the first two being the father and uncle of the more famous Marco), Florentines, Spaniards, Portuguese, Frenchmen, Britons, Germans, Moroccans (Ibn Battuta) and the famous Franciscan monk William of Ruysbroeck from the Flanders, among others.

I spent a couple of days in Dun Huang, a historic town on the Old Silk Road, next to the Gobi desert, famous for its ancient Buddhist grottoes. There is also a substantial Muslim presence in this region — Lanzhou is 20 per cent Muslim. It is evident that the Old Silk Road was a conduit for the transmission of religions and cultures, and not just commerce.

The Old Silk Road may have been cosmopolitan, but it did not partake of a globalised world in the way that its contemporary equivalent does.

China’s Road and Belt initiative will certainly represent an intensification of globalisation, as it modernises several less-developed regions in this display of Chinese ‘soft’ power intended to counterbalance in a much needed way the United State’s baneful world-wide hegemonic display of ‘hard’ power and military muscle.

But there can be lags in this impressive modernisation.

Accompanied by my Chinese guide, I went to the post office three times to mail touristy postcards to family and friends in the United States and United Kingdom. I had to show my passport to the clerk before I was allowed to buy stamps, each postcard was then weighed, and the stamp-purchase for each postcard was finally entered manually into the clerk’s computer. A postcard cost 6 yuan to mail, but there were no stamps in exactly this denomination, so I had to buy 3 stamps — ¥4.20, ¥1 and ¥0.80 — to get the requisite 6 yuan. The transaction took 15 minutes when it should have taken 2–3.

China is technologically more advanced than the United States in many ways: a maglev train capable of reaching speeds of 373mph/600kph will go into production in 2021, also bridge design and construction, synchronised traffic-light systems, cell-phone technology, household electronics, alternatives to carbon-based energy, but I’ve been to Third World countries where scanners are used to expedite greatly such postal transactions, as well as not requiring ID in order to sell someone a few stamps for their postcards!

Another post office I went to had run out of all its stamps. Yet another post office told me, or rather my Chinese guide, that I only needed ¥5 for each of my postcards, which left me confused because I had paid ¥6 in the post office I’d been to previously. I hope those postcards with ¥5 stamps reach their destinations.

On the plus side, China’s post offices also serve as banks, a boon to the public many western countries — with their rip-off banking systems — should see the need to implement for themselves.

However, a country which has (for example) built the world’s longest bridge and its fastest trains deserves a better ground-level postal service.

As I was leaving the country, China reported its slowest economic growth in 26 years — its economy grew by 6 per cent for the three months ending in September. A fall in domestic demand was partly responsible, but the main factor was the sharp fall in China’s exports to the United States, its biggest foreign market, due to Trump’s trade war.

Exports to the United States fell a remarkable 21.9 per cent in September compared to a year ago, while imports of American goods dropped by 15.7 per cent. The US economy is of course being hurt just as much, if not more, by the tariff war.

There is probably no serious cause for alarm here — 6 per cent is more than twice the US growth rate and about three times that of the western European countries. Moreover, falling growth rates carry with them some benefits for the environment since the prevailing rate of resource depletion will also be slowed down.