ASEAN leaders hold summit with Myanmar’s general shut out

- Update Time : Monday, October 25, 2021

- 60 Time View

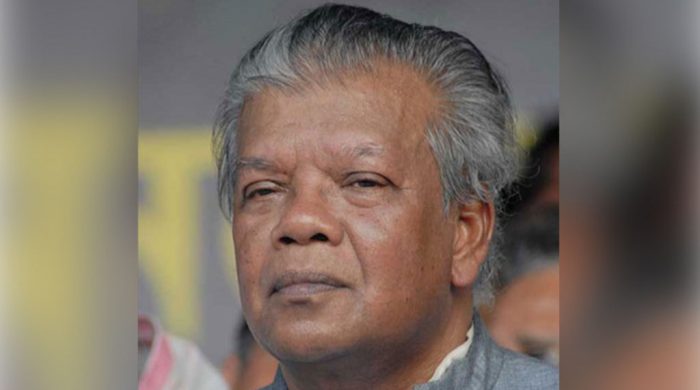

Southeast Asian leaders are meeting this week for their annual summit where Myanmar’s top general, whose forces seized power in February and shattered one of Asia’s most phenomenal democratic transitions, has been shut out for refusing to take steps to end the deadly violence.

Myanmar defiantly protested the exclusion of Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who currently heads its government and ruling military council, from the summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Brunei, which currently leads the 10-nation bloc, will host the three-day meetings starting Tuesday by video due to coronavirus concerns. The talks will be joined by President Joe Biden and the leaders of China and Russia, and are expected to spotlight Myanmar’s worsening crisis and the pandemic as well as security and economic issues.

ASEAN’s unprecedented sanctioning of Myanmar strayed from its bedrock principles of non-interference in each other’s domestic affairs and deciding by consensus, meaning just one member can effectively shoot down a group decision. Myanmar cited the violation of those principles enshrined in the group’s charter in rejecting the decision to bar its military leader from the summit.

But the regional group has few other options as the general’s intransigence further risked tainting its image as a diplomatic refuge for some of the most intractable tyrants in Asia.

A senior ASEAN diplomat, who joined an Oct. 15 emergency meeting where the foreign ministers decided to rebuff Myanmar, said those two principles bind but “will not paralyze” the bloc. The diplomat called ASEAN’s more forceful response “a paradigm shift” but added its conservative principles would likely stay.

“In serious cases like this, when the integrity and credibility of ASEAN is at stake, ASEAN member states or even the leaders and the ministers have that latitude to act,” said the diplomat, who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because of a lack of authority to discuss the issues publicly.

Instead of Myanmar’s top general, the country’s highest-ranking veteran diplomat, Chan Aye, was invited to the summit as the country’s “non-political” representative, the diplomat said. It remains unclear if Chan Aye will attend.

Myanmar’s military-appointed foreign minister joined the online emergency meeting two weeks ago. It was held in a calm manner, although some ministers bluntly expressed their opposition to the Feb. 1 military takeover that ousted civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, which overwhelmingly won last November’s vote. Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan declared that his government still recognizes Suu Kyi and ousted President Win Myint, both of whom have been detained, as Myanmar’s legitimate leaders, according to the diplomat.

Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah, a staunch critic of the military’s seizure of power, told his ASEAN counterparts that the principle of non-interference cannot be used “as a shield to avoid issues being addressed” given that the Myanmar crisis has alarmed the region. In a separate online forum last week, he suggested officials and others “do some soul-searching” for ASEAN “on the possibility of moving away from the principle of non-interference toward `constructive engagement’ or `non-indifference.’”

ASEAN has been under intense international pressure to take steps to help end the violence that has left an estimated 1,100 civilians dead since the army took power and locked up Suu Kyi and others, igniting widespread peaceful protests and armed resistance. U.N. special envoy Christine Schraner Burgener warned last week that Myanmar “will go in the direction of a failed state” if violent conflicts between the military, civilians and ethnic minorities spiral out of control and the democratic setback was not resolved peacefully.

Suu Kyi’s party won in a landslide victory in 2015 after more than five decades of military rule. But the military remained powerful and contested her National League for Democracy party’s win in last November elections as fraudulent.

ASEAN has not recognized the military leadership although Myanmar remains a member.

The group “must take a bolder step to speak up against non-democratic overthrow of democratically elected government and crimes against humanity against the Myanmar people,” said Alexander Arifianto, an Indonesian expert on regional politics at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. “ASEAN needs to reform its decision-making process.”

ASEAN leaders agreed on a five-point contingency plan in an emergency meeting in April in Indonesia that was attended by Min Aung Hlaing. They called for an immediate end to the violence and the start of a dialogue to be mediated by a special ASEAN envoy, who should be allowed to meet all parties. But the military later repeatedly refused to allow the envoy to meet Suu Kyi and other political detainees in an impasse that is testing the regional bloc.

ASEAN admitted Myanmar in 1997 despite intense opposition from the U.S. and European countries, which then cited its military junta’s record of suppressing democracy and human rights. The other members of the bloc are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.