Legitimacy deficit haunts Lanka govt

- Update Time : Wednesday, September 27, 2023

- 37 Time View

THE country to which president Ranil Wickremesinghe returned after his international successes in the Americas remains in dire straits. In both Cuba and New York, the president made his mark at the podium holding his own with giants on the world stage. Addressing heads of state at the G77 Summit in Cuba, the president spoke of the significance of science, technology and innovation in shaping the future of developing nations. He referred to the new technological divide emerging in the 21st century, necessitating the adoption of digitalisation and new technologies, such as Big Data, IoT, AI, Blockchain, Biotechnology and Genome Sequencing, to bridge the gap. He also reaffirmed Sri Lanka’s commitment to supporting the new Havana Declaration and called for the collective voice of G77 and China to be heard in international fora.

Addressing heads of state at the UN General Assembly, the president drew upon his experience in peacebuilding when he called for the expansion of the UN Security Council’s composition as essential for world peace. He also highlighted the reforms he initiated in the economic, financial, institutional and reconciliation fronts as being directed towards rebuilding trust and confidence between the people and the government and as laying the foundation for economic stabilization and recovery. However, the president faces formidable challenges in this regard. The country’s economy, which shrank by over 7 per cent last year and by 11 per cent in the first quarter of this year, continued its downward plunge with a further shrinkage by 3 per cent in the second quarter. The much touted absence of shortages and queues is not due to the economic performance picking up but because people have less money to spend.

With inflation in the past year having halved the real income of people, and high taxation of those in the tax net further impoverishing those in the middle income and professional categories, they are leaving the country in droves leaving behind gaping holes in various sectors of crucial importance to the economy. But the tax reforms that have impacted on the middle and professional classes directly and the increased sales taxes that have impacted on the poor are still not covering the gaping hole in the country’s finances that need to be filled for IMF support to be forthcoming. Government revenue has seen a shortfall of Rs 100 billion as compared to the revenue target agreed with the IMF. There is a clear need to utilise tax money in a more streamlined way without it being misallocated or pilfered on a large scale which is widely believed to be a continuing practice in the country.

Inequitable burdens

THE indications are that further economic hardships will need to be placed upon the people. The problem is that the government is placing the burden disproportionately on the poor and not on the rich. Dr Nishan de Mel who heads the Verite Research think tank that has been doing in-depth analyses of Sri Lanka’s encounter with the IMF disagrees with the government’s position that banks would collapse if the banking system had to bear some burden of domestic debt restructuring. He points out that this conclusion had been reached without any analysis. ‘All the other countries that restructured debt shifted part of burden debt restructuring on to the banking sector. There are ways of protecting banks during debt restructuring. The government has placed all the burden on the pension funds and says that the impact on these funds is limited. It also claims that banks will collapse if they are affected by domestic debt restructuring. So, which claim is true? Why can’t the banks share part of the burden?’

There is a general consensus that the burden of economic restructuring is falling disproportionately upon the poorer sections of society. Dr de Mel has also pointed out that the government has been privatising profits while socialising losses because of the lack of accountability. ‘When those in power work for the benefit of themselves and their friends, they ensure that a small group of people enjoy the benefits of growth or implement policies that benefit targeted groups. However, when things go wrong, for example, when we have to restructure domestic debt, those in power make sure that the people in general bear the losses. This is what we have seen in Sri Lanka.’ This view is also to be seen in a Civil Society Governance Diagnostic Report produced by a collective of civil society organisations and authored by Professor Arjuna Parakrama which states that ‘The current growing sense of economic injustice has been exacerbated by the fact that the architects of the economic crisis do not bear any part of the burden of its proposed reform, which has been, again, firmly thrust, without any public dialogue, on the victims of this very crisis.’

Making the situation more prone to instability is the fact that this inequitable burden sharing is being done by a government that has little political legitimacy. Barely a year and a half ago, those who are currently ministers in the government were on the run, hiding from the wrath of vast multitudes of people who were demanding that they be held to account for having bankrupted the country through their corrupt and venal deeds, whether real or imagined. All of those who are now ministers (with the exception of a handful who have crossed over from the opposition) were compelled to resign from their ministerial positions. They were legally reappointed by president Ranil Wickremesinghe after he was legally elected president by the votes of 134 parliamentarians. But a legitimacy deficit continues to haunt the government and makes it an insecure one though presently firmly ensconced in power. The way to gain legitimacy to bridge the trust deficit is to be fair and just in making decisions that impact upon all the people.

Undemocratic laws

UNLESS remedial steps are taken the government’s current engagement with the IMF may be difficult to sustain. This is not only because the government is failing to meet the targets set by the IMF. There is also a lack of confidence about the IMF programme among the general population. A public opinion survey conducted by Verite Research has shown that about 45 per cent of Sri Lankans believe the IMF will make things worse for the economy in the future. Only 28 per cent of the population believes Sri Lanka’s ongoing programme with the IMF will make things better for Sri Lanka’s economy in the future. The mounting difficulties faced by people in coping with their economic circumstances can lead to protests and agitation campaigns. The logic of competitive electoral politics can also come into play with different political parties making their own promises to alleviate the economic hardships on the people even at the cost of the economic reform programme agreed with the IMF.

There appear to be trial balloons put out by government members that safeguarding the IMF programme may require a moratorium on elections. The government has shown itself willing to take this route ostensibly for the sake of the economy. Even before the agreement with the IMF, the government postponed local government elections that had been set for March of this year citing the need to focus on economic recovery rather than hold elections. Recently, MP Vajira Abeywardena, chairman of the UNP of which the president is the leader, has stated that the government would not be able to meet the economic needs of the people if funds were allocated through the 2024 budget for the presidential election which is due in a year. The emergence of two controversial laws that can restrict freedom of expression and the ability to engage in public protest may need to be seen in this context.

The draft Anti-Terrorist Act which seeks to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act is wider in scope and gives the government the power to arrest persons who are engaging in public protest or trade union action. Those who are charged as ‘intimidating the public or a section of the public’ can be arrested under this law. The Online Safety bill has the potential to curtail the use of the internet for political communication purposes. It will establish a five-member commission, all of whom will be appointed by the president, and they will be tasked with determining the veracity of online content. The commission appointed by the president will be able to proscribe or suspend any social media account or online publication, and also recommend jail time for said offenses. The Bar Association has said that both these draft laws seriously impinge on the liberty and freedom of the people, will have a serious impact on democracy and the rule of law in the country and called for their withdrawal. If these two laws are passed by parliament, they will make it more difficult to challenge the government even when it is going on a wrong path. But with the economic situation continuing to get worse, and the suffering of vast masses of people increasing, repression through the use of law and the security forces will not be a sustainable option.

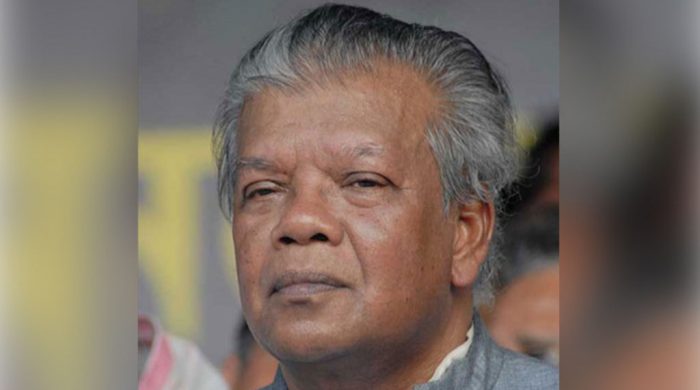

Jehan Perera is executive director of the National Peace Council of Sri Lanka.