The curse of identity politics

- Update Time : Saturday, October 14, 2023

- 39 Time View

Unusual public criticism of India by Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau following the murder of a Sikh separatist in Canada has once again focused international attention on the movement for a separate Sikh state, writes Mohammad Luqman

THE name Punjab is of Persian origin and means ‘land of five rivers’. The region has long been described as the breadbasket of the Indian subcontinent. Good irrigation and a warm climate yield several harvests over the course of a year. Over the millennia, the idyllic villages with their traditional clay structures and lush green fields have fostered a unique culture that unites the wide-ranging cultural influences that lend Punjab its character.

Partition of the subcontinent in 1947 allocated the majority Muslim West Punjab to Pakistan, while eastern Punjab, which was mostly inhabited by Sikhs, was assigned to India. This division resulted in outbreaks of violence, displacement and the destruction of established communities on both sides.

Despite this traumatic event, even after almost seven decades, both parts of Punjab are still deeply intertwined on cultural and linguistic levels, much more than many might think. Among the western diaspora in particular there is a growing sense of kinship between Punjabis from both nations, something that seems barely conceivable considering the current political climate on the subcontinent.

In Bollywood films, Punjab is often portrayed as the home of the vivacious Sikh minority. The Sikhs are members of a syncretic religious community that unites elements of Islam and Hinduism and was founded by Guru Nanak Dev, a 16th-century saint and ascetic. From the 18th century, various Sikh militias captured large swathes of Punjab and founded their own kingdom, itself captured by British colonialists in 1849.

In the early 20th century, during the Indian independence movement and under the leadership of Jagjit Singh Chauhan, the first nationalist Sikh movement emerged aimed at establishing a Sikh state of “Khalistan” across large areas of Punjab.

Sikh nationalism

ALTHOUGH initially, such aspirations ended with the incorporation of eastern Punjab into Indian territory, the idea remained popular with many Sikhs. The nineteen-eighties saw a revival of the separatist Khalistan movement.

Clashes between Sikh activists and the Indian state as well as the division of Indian Punjab ordered by central government led to a growing sense of marginalisation among Sikhs. The Khalistan movement also received generous financial support from the Sikh diaspora in the west.

The mood was darkened further by the dire economic situation in Punjab and the high rate of youth unemployment among Sikhs. From 1982, Punjab experienced a wave of violence at the hands of Sikh separatists.

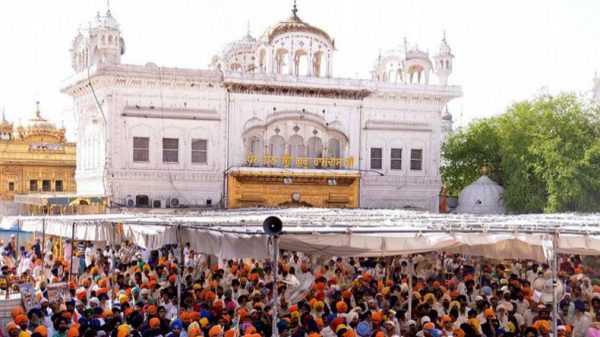

When several fighters holed themselves up in the Golden Temple of Amritsar in 1984, Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi ordered the army to storm the shrine. Operation Blue Star, as the attack was named, lasted almost 10 days.

The deployment of heavy artillery resulted in the destruction of much of the temple complex causing outrage in the Sikh community. In response, Sikh bodyguards murdered the Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi.

This in turn triggered nationwide pogroms conducted by Hindus against the Sikh minority, in which thousands more people were displaced or killed. The government struggled to bring the violence under control. In the collective memory of the Sikh minority, Operation Blue Star remains a profound trauma to this day and is recalled as one of the bleakest chapters in the community’s history.

Growing disaffection in Punjab

SUPPORT for the Khalistan movement gradually subsided in the 1990s. However, it has regained popularity in recent years under the Hindu nationalist BJP government. This is due to the BJP’s policy programme aimed at the ‘Hinduisation’ of India. Many Sikhs fear this will further marginalise their minority, reflecting the experience of other religious minorities in the country.

A clear expression of this disaffection were protests against Prime Minister Modi’s planned agricultural reforms in the year 2021. Sikh farmers in Punjab saw the reforms as a threat to their livelihoods. Since then, Sikh separatists have regained some traction, as evidenced by the case of the Sikh preacher Amritpal Singh early this year.

Thirty-year-old Singh is a popular preacher who perceives himself within the tradition of the Khalistan movement. At the start of this year, the Indian government deployed thousands of police officers and paramilitaries to arrest the well-liked preacher, accusing him of separatist activities. His detention is an indication of the BJP’s tougher crackdown on political activists and critics at home.

Diplomatic tension

IT IS a pattern that has been repeated in a series of dramatic murders of Sikh separatists abroad. In May 2023, for example, the Sikh Paramjit Singh Panjwar was shot dead in unexplained circumstances in the Pakistani city of Lahore. The murder of the pro-Khalistan activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in the Canadian city of Surrey in June of this year has again focused international attention on the Khalistan movement.

The Canadian Prime Minister publicly accused the Indian government of direct involvement in the murder of Nijjar. Diplomatic tensions between the two nations have increased markedly ever since. Canadian intelligence agencies claimed to have concrete evidence of the involvement of Indian agents in the Sikh preacher’s murder.

They may also have received information from other western secret services. India denies any involvement and in turn accuses Canada of harbouring Sikh terrorists.

The political crisis between the two nations is not yet over. It does however illustrate how the Hindu nationalist BJP government is stepping up its crackdown on critics. On October 3, critical journalists were arrested in New Delhi under the draconian anti-terror UAPA (Unlawful Activities Prevention Act). For activists, a confirmation of their fears that the BJP government is gradually turning India into an authoritarian state.

Qantara.de, October 10. Mohammad Luqman is a scholar of Islam and South Asian specialist. The piece is translated from German by Nina Coon.