Civil society divided over denial of entry to Rohingyas

- Update Time : Tuesday, February 13, 2024

- 19 Time View

Civil society members are divided over Bangladesh’s position on allowing repressive Myanmar troops and rejecting shelters for persecuted Rohingyas fleeing adverse situations in conflict-ridden Rakhine.

Some of them said that no more Rohingya should be allowed as no genocidal acts were reported in Myanmar in recent times that could force them to seek shelter in Bangladesh, while rights activists were critical of rejecting Rohingyas.

The rights activists called it the ‘double standard’ of the country when it has already sheltered more than a million Rohingya who fled Myanmar due to persecution.

At least 330 members of Myanmar’s Border Guard Police, Myanmar army, immigration officials, police, and members of other agencies entered Bangladesh between February 4 and 9, while the Border Guard Bangladesh rejected the entries of 75 Rohingya who wanted shelter around the same time.

Bangladesh government officials said they allowed fleeing Myanmar troops as they would be repatriated soon.

Asked whether the government would open the border to allow Rohingya people reportedly waiting on the other side of the bordering river Naf, like fleeing Myanmar troops, foreign minister Hasan Mahmud said at a briefing in the ministry on Monday that Bangladesh was already hosting around 12 lakh Rohingya, who were creating various problems, including putting security and the environment at risk and getting involved in drug smuggling.

After reviewing security at the Naikhyangchari bordering area, the newly-appointed BGB director general, Major General Mohammad Ashrafuzzaman Siddiqui, told the media on February 7 that no more Rohingya refugees would be allowed to get into Bangladesh.

Both the BGB and Bangladesh Coast Guard, with heavy military weapons, were seen patrolling the Naf River and adjacent border to prevent any ‘infiltration’ through the border.

Besides, Obaidul Quader, the minister for road transport and bridges and general secretary of the Bangladesh Awami League, told reporters on February 7 ‘We will not allow any more Rohingya to enter the country… they have already become a burden for us.’

M Touhid Hossain, former foreign secretary of Bangladesh, told New Age that Bangladesh allowed defeated soldiers, assuming that Myanmar would definitely evacuate them, but was not sure about Rohingya as long as over one million of them were currently living in Bangladeshi camps.

‘I personally think no more Rohingya should be allowed,’ he said.

Kazi Reazul Haque, former chairman of the National Human Rights Commission, said that in the past, Bangladesh allowed Rohingya on humanitarian grounds, and now they are a burden for Bangladesh.

He argued that Myanmar forces were part of their government, so they were allowed to be sent back.

Shahidul Haque, the immediate past foreign secretary of Bangladesh, during whose service a major Rohingya influx took place in 2017, declined to comment when asked about allowing Myanmar forces and rejecting Rohingyas.

Dhaka University’s international relations department’s retired professor, Imtiaz Ahmed, also claimed that allowing Myanmar troops and rejecting Rohingya were not the same.

He argued that they had not received any information from independent sources about any fresh persecution of Rohingya in Myanmar since the International Court of Justice issued provisional measures to protect Rohingya.

On January 23, 2020, following the Gambia’s application, the ICJ issued provisional measures against Myanmar to prevent any genocidal acts in its territory against the Rohingyas and to protect them.

Sultana Kamal, the founder president of the Manabadhikar Shongskriti Foundation, also said it has to be ‘critically assessed’ whether to allow or reject any more Myanmar nationals into Bangladesh.

She insisted that, despite the burden, there is a human rights cause for the Rohingya issue.

John Quinley, director at Bangkok-based Fortify Rights, told New Age that not allowing Rohingya refugees into the country was ‘absolutely outrageous and inhumane.’

‘Rohingya are fleeing ongoing attacks inside Myanmar from the junta and the Arakan Army. They are caught in the middle of a conflict and must be given protection,’ he said.

‘Dhaka is taking an unjust approach to refugee protection. They should not push any new arrivals away,’ he added.

Prominent Bangladeshi human rights worker Mohammad Nur Khan also criticised the move to allow armed soldiers and reject unarmed civilians from the same country.

‘It is nothing but a double standard for the Bangladesh government,’ he said.

Mohammad Ashrafuzzaman, a consultant at the Australia-based Capital Punishment Justice Project, said allowing armed soldiers and rejecting unarmed civilians of the same country was happening at a time when the Bangladesh government was credited worldwide for hosting the Rohingya population.

‘This government is showing double standards,’ he concluded.

Shayna Bauchner, Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, noted in their latest report published on February 9 that in late January, between 12 and 24 Rohingya civilians were killed in Myanmar, while as many as 100 more may have been injured.

More than 100 homes were believed to have been damaged or destroyed, said the researcher, citing Rohingya groups.

Some residents described the Myanmar military’s airstrikes on their village as indiscriminate bombardments, the report said, adding that Rohingya families expressed concerns about food stocks dwindling and unharvested crops rotting in the fields.

According to Rohingya villagers, the report said that all the beds in the hospital in Buthidaung in Rakhine and local clinics were filled and that the facilities had stopped admitting people.

‘Clinics were running low on supplies and charging injured patients exorbitant prices.’

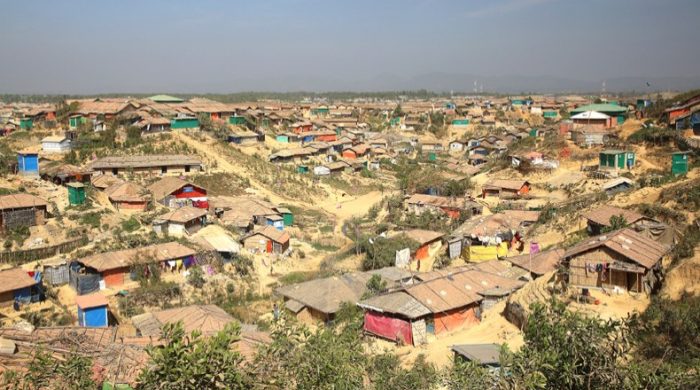

More than 700,000 Rohingya fled the Myanmar military’s crimes against humanity and acts of genocide in 2017.

About 600,000 Rohingya remain in Rakhine State, confined to squalid camps and villages under a system of apartheid in which security forces have arrested thousands of Rohingya for ‘unauthorised travel’ and imposed new movement restrictions and aid blockages.

This has left the Rohingyas particularly vulnerable to armed conflict, the report said.